There are moments in life, usually of the big turning-point sort, where you are able to look back and realize that everything that has happened in your life has prepared you for this. As I sat with Florence Sitruk in the small harp studio of the Jacobs School of Music building at Indiana University in Bloomington, it was clear that the gravity of the moment was still sinking in. This small, somewhat spartan room on the ground floor doesn’t have a stunning view or lavish furnishings (aside from the two concert grand harps). What the room does have is history—for years, room 003 was the studio of Susann McDonald, the legendary harp teacher at IU who retired last year after more than 30 years at the school. “There is music in these walls,” says Sitruk, fondly. Now it is Sitruk’s name that has replaced her mentor’s on the door of room 003. Seeing her name on the door—a door she had passed through countless times as a student there 20 years ago—was the moment she knew it was real. She had landed perhaps the most prestigious teaching position in the United States.

Harp Column: You have been teaching for years, and now you find yourself in Bloomington at one of the premier harp programs in the world. Tell us a little bit about what it is like for you to come back to Bloomington as a teacher.

Florence Sitruk: There is this knowledge that something is very beautiful and magical, but it doesn’t mean you understand. I didn’t understand until I came to this door, and my name was on the door. It was a shock. I must say, there are two layers to it. One layer is returning to Bloomington. It does help me a lot that I was here as a student, that I understand the aspirations of the young ones, that I can think of it from the student’s side. The other layer, which I think is also unbelievably important, is understanding the unmatchable legacy of Susann McDonald. I think if we take everyone together who ever had a chance to study with her, we still could not match up to what she means and the light she is. My hope is to bring [this program] into the future in her honor, but of course, I’m coming with my backpack, so to speak. I come from a different origin, and I was raised in a different country. We say that music is an international and global [language], and I think we are [international] as artists, musicians, and people. But the way someone from Iceland plays Mozart sounds completely different from someone who comes from Australia. [These different regional characteristics are] very beautiful. It was important to me at the Geneva University of Music that my class consist of students from many different nations. We would discuss what it means to have a different background. Maybe somebody from Russia likes a little bit less to play music of the 20th Century, but would beautifully play Romantic music whereas, with the French, it was the opposite—[they might prefer more] Baroque music. We spoke about that and tried to put into words what it means where you come from. I hope that this backpack I bring with me helps the students here at Indiana. I do know that the eyes are on the IU harp department, that’s for sure.

HC: You mentioned that where someone comes from is important in how it influences their music. How do you think your upbringing has shaped you as a musician?

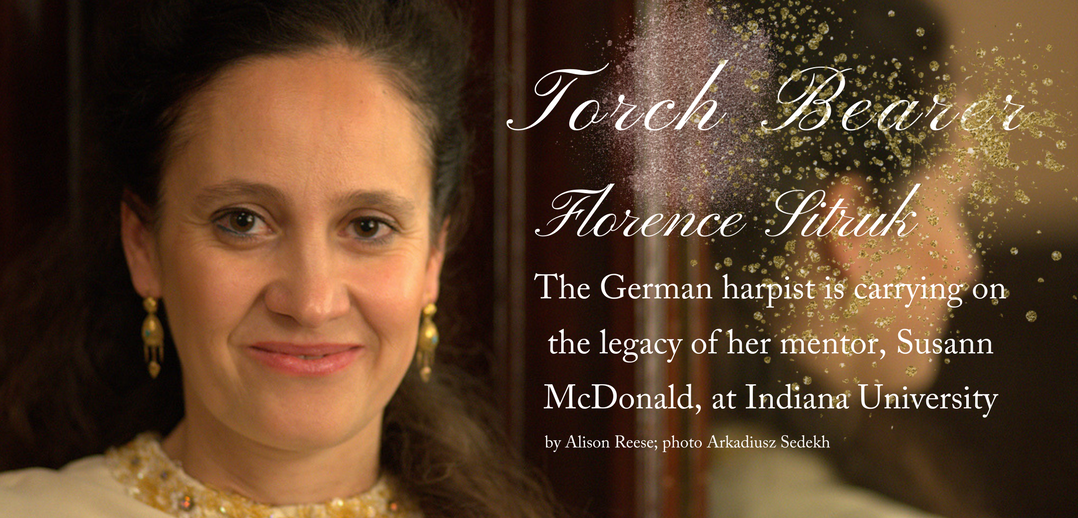

The facts on Florence

A native of Southern Germany, Florence Sitruk took up the harp at age 6. At age 12, she entered the University of Music Stuttgart with Therese Reichling. She continued her studies with Tatiana Touer in Spain and Marielle Nordmann in Paris, before graduating with Susann McDonald and György Sebök at Indiana University with an Artist Diploma. She also studied early music, musicology and philosophy at Freiburg University. Winning first prize at Bucchi International Harp Competition in Rome led to her debut with the Berlin Philharmonic in 2001. She has since given the national premieres of Parish Alvars’ harp concertos in many countries, including Brazil, Morocco, and Lithuania and has concertized in 36 countries with longtime partners, such as mezzo-

soprano Stella Doufexis, the Ciurlionis String Quartet, and flutist Lukasz Dlugosz.

She has been harp professor at Geneva (Switzerland) Haute Ecole de Musique since 2005, and a guest professor at the Krakow (Poland) Music Academy since 2014.

Upon Sitruk’s appointment at Indiana University in 2017, her husband, violist Guy Ben-Ziony, auditioned and won a position with the Bloomington-based Pacifica String Quartet.

FS: That’s a good question—a big one. My parents are non-musicians, but I find them very musical people. My father speaks a lot of languages; my mother is very precise about etymology—where things come from, their origins. They are both very curious and very open-minded to the world in general. So I think that’s something very important for becoming a musician. They both didn’t want me to be a musician, though, so I had to struggle hard to find my way and even convince them, and I’m very proud I could. [Laughs]

HC: This sounds like quite an accomplishment.

FS: My father is an engineer—he works with big hydraulics and cranes that fortify walls for heavy storms—and he would say, “Well, I have to do this work, so you carry your harp.” I could never just say, “Oh, Daddy, carry my harp.” And my mother wanted me to be in languages or international relations—that was where she was successful. But I did something completely different. The area I come from [in Germany] is the Black Forest. The Black Forest is beautiful. It’s a very old landscape, and the people who live there are all from mixed backgrounds. There is a lot of Latin influence, and you see it in the way people look—they have dark hair and blue eyes, which I didn’t get. [Laughs] They are very Roman and Latin. Even the dialect we speak has 30 percent of the Latin language. And we have 30 percent of the old French language. We have a rich linguistic heritage, which is something that makes this area very special. The people of the Black Forest also have a history as freedom fighters—independent of spirit—and strangely, a lot of professional musicians come from that area, including big stars like Anne-Sophie Mutter, the violinist; Tabea Zimmerman, the violist; and many more. We don’t know why. Tabea Zimmerman thinks it’s the good red wine. [Laughs] We have much more sunshine than anywhere else in Germany, and it’s much warmer. Depending on which way you drive, in an hour you can be in France or Switzerland, and in four hours you can be in Italy. I think it’s obvious how much this open landscape influences you.

HC: What feels like home to you?

FS: Oh, I think it’s always defined by human beings; I don’t think it’s a specific place. It’s where you feel that you are being seen and loved, and where your mother tongue is. Of course, it’s where my children are. Here in Bloomington, last night it was my first time driving by myself home, and I got lost. I stopped to ask someone for directions, and when I looked at him, I said, “I know you from somewhere.” He was here 20 years ago as a guitar student [when I was here as a student], and he’s now the guitar professor. That made me feel at home. I love these coincidences and the human connection.

HC: Tell us about the other schools where you have taught. You’re still teaching in Geneva, but do you plan to continue that?

FS: My teaching “apprenticeship” was in Lithuania. At the time, I couldn’t have dreamed how important that experience would become to me. I was 25 and was invited to play with a wonderful string quartet from Lithuania. A gentlemen in the audience, who happened to be the director of the school, asked me if I would be interested in teaching harp at the Academy. It was a huge honor, but I had no idea what to expect. There was no modern concert harp. We had old Russian harps whose strings had not been changed in a long time. There were no strings. There was no library. What they did have were hugely gifted young harpists; the lady who taught and played there before was so gifted. She really knew how to put their hands on the strings in the perfect way. So I had to deal with finding sponsorship, building a library, and coming up with a way to support them. There were no resources I could rely on. My time there really packed my suitcase with skills. Still today, sometimes, I am shocked when my students come in with these new editions, and everything new—my Lithuanian students just couldn’t buy those things. We got a harp sponsored by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs in Germany—the first harp that they ever sponsored for another country. We got Lithuania into the World Harp Congress, and now we have international prize winners. Agne Keblyte won second prize in [the International Harp Contest in Israel], and she’s one of Lithuania’s many tremendous talents. It’s a great treasure for a teacher to experience that so early. So on the one hand, the level of talent was very high, and demanded a high level of teaching to match it, but on the other hand, there was just no equipment. That experience gave me a great backbone for Geneva, where I had to deal with institutional things and also sometimes limitations. Because Switzerland is not in the EU, it’s very difficult for the young people to get scholarships, and it’s an expensive place to study. So these were difficult things to handle, but I was able to draw on my experiences in Lithuania to find ways to work around these difficulties. I’ve been in Geneva for 13 years, and it felt like a good time to change. When I applied [for the position at IU], I didn’t expect anything. I thought it would be a brush up at 42 to compete and see where you stand. I owe it to a friend who was with me when I was at IU who urged me to apply because it was not on my radar. He kept calling every day, “So did you apply?” I said, “No.” He said, “You do it; do it now.” I said, “No, my English isn’t good enough. For sure not.” And he said “No, you go.” Really, he called every day. Now he’s so proud. He was my college sweetheart here in Bloomington, and he’s now a very good cellist in Belgium.

HC: Who have been the biggest musical influences in your life?

FS: Susann McDonald, for sure. Also György Sebők, the Hungarian pianist who was upstairs [from the harp studio at IU]. And in a completely different way, Marielle Nordmann. She was the harpist I heard at the age of 5 or 6 in a concert. I had already started to play the harp, and she was the first harpist I heard live. She became my favorite harpist and musician. I love her sound, and I find her style of playing so profound. I love how her thinking translates to her music-making—it is something unmatched. She was not the foremost pedagogue in my life, but she was the foremost musician. She would not tell you what to do; she would not change your technique. She would not be regular as a teacher; she was always on tour, she had three small children. She was an artist from the beginning of the day to the end, and I think it’s something to admire, how she always remained that artist, independent from academia, from recording companies, from anything. She also managed to have a beautiful family life. She used to tell me that, in the first 10 years after having children, she would always make sure she returned the next day after giving a concert. Her balance of career and family set an important example for me. I made sure I was there for my kids the next morning. She helped me see the possibilities.

In terms of musical and pedagogic influence, however, no one can surpass Susann McDonald. One of her ideas that has influenced my teaching is giving students weekly performance opportunities—in studio class—I find that very important. These are young colleagues of the future, who will eventually hold positions all over the world, and they need to learn to work together. This studio needs to be an open house, to be tolerant, to have an openness to share information, to let anyone listen here. Susann McDonald for me, above all, is an unfailing musician. You can have methods, you can believe this or that, but at the core, you must just be a wonderful musician, and this is what she is for me, and of course much more.

HC: What kind of student were you at IU?

FS: I don’t think I was her most conscientious student at the time. I think I was even a bit naughty and questioning. I came from Paris, and I didn’t quite understand American life. I didn’t understand the campus, and streets, and addresses, [Laughs]. Goodness, she was so generous, and she let me be naughty. [Laughs]. She was very open to transcriptions I brought, and I think she had such a big heart, while also having such high expectations. When she found out that I loved to go to György Sebők’s masterclasses, she supported it. She knew that I was taking private lessons with him on piano music, and there are teachers that say, no, you can’t study with anyone else. But she was so generous and so open and not controlling, as long as you worked to the highest level. That taught me a lot. I think this is how you have to serve students—try to find their voice. About György Sebők, I could talk for ages. I think he is very special because people either know him and speak very highly of him, or they don’t know him at all. There is no in-between. He was like an x-ray. He would sit there, and you had the impression that within minutes he would know you inside and out. He would always try to find out why you think the way you do. He would never say, “It has to be like this.” He wanted you to understand how you maybe got on the wrong path. To give you an example, in a masterclass there was a young pianist who played Franz Liszt brilliantly—everything flawless, everything perfect, but with a very stiff neck. And Sebők just said one sentence: “It seems you don’t want to lose your head.” He had this wonderful translation of pictures and this wonderful paradox we are in all the time as musicians. One mind goes into the future, and the other mind is here, and you need to know what to do right now, but you also have to think ahead in your musical mind. He was able to name all of these musical paradoxes. I don’t think you could ever match up to what his hands were thinking. I will miss him all my life.

HC: Now, you were studying piano transcription on the harp with him, correct?

FS: Yes, but you know, he would sit down and play the Parish Alvars Serenade on the piano with the most beautiful sound you could imagine. He had a harp sound on the piano. He showed me how to play harmonics. He said, “If you drop them they can’t sound. It’s the other direction.” He sight-read the Salzedo Variations on the piano—it was fantastic. [Laughs] He was a grand master. And he was a humanist through and through. He was a true philosopher and also witty, and very sharp in his observations. We lost him much too early. I feel so fortunate that I had these two teachers at IU, and Marielle Nordmann as a musical influence and a link to the musical heritage of Lily Laskine. The older I become, the more I understand the importance of these influences.

HC: You enjoy vibrant careers in both teaching and performing—how do you think your performing influences your teaching, and how does your teaching influence your performing?

FS: Right now, I’m in a transitional phase thinking about that. Generally, I would say you need to be or have been a performer to understand what makes the teaching important. But also, I think being a performer is the basis for understanding what young people go through. You are on stage, in the middle of the storm, and no one is going to take that responsibility for you. We need to encourage students and train them to find their full abilities in that moment. It has nothing to do with exams, and it has nothing to do with doing things right and pleasing your teacher. It is really finding happiness in that moment. How to get there is a big thing—how to walk off stage and be able to say, “This was the Hindemith or Debussy I wanted to play tonight.” I think we all know how rare this is. How to locate this within academia where it is important to have good grades is another topic, but we always need to translate that good grades mean finding your greatest potential in the moment you are performing. Of course good technique is important, but it’s much more than that. So I think that is where performing is important to teaching.

I have learned a lot from my students, of course, sometimes by their questions, sometimes by their way of doing things differently. When they are advanced, when they are at this age where they start questioning and do not just follow a fingering or just follow advice, but ask, “Why?” That is when we can discuss things together. I love that. That’s around 22 or 23 usually. It’s like a second freedom they are entering, and I know this is the moment when they will soon break free and be independent. So this is where it really inspires me. To give you an example. Last semester in Geneva, I offered a seminar on the Mozart Concerto with all its details—when it was written, why it was written, what the questions are about it, and the problem of the tempo in the first movement. The goal was for the students to write a cadenza themselves at the end of the seminar—what should it look like, should it be historically informed or something totally different—and by the time we had finished, I was convinced that I shouldn’t play a cadenza in the third movement. When I performed Mozart recently I didn’t. The flutist and I decided to play one transitional measure, and no more cadenza, and it felt so good. It took me how many years to decide that? And it was because of the work with my students. I was lucky to see the original [manuscript] in Krakow, and I broke into tears to see the handwriting of this 22-year-old man. It also solved my question about the tempo in the first movement. You clearly see that the arpeggio, that is rhythmically noted, is before everybody plays. It’s not an appoggiatura, it’s not before the beat, but it’s before the orchestra so the orchestra knows your tempo, and there’s no excuse for playing it too fast. The harpist sets the tempo. I didn’t understand it that way from the print. Ever since this experience, I am now trying to play everything from the handwritten music—C.P.E. Bach, J.S. Bach, Scarlatti—I want to see the handwriting. It changed everything. It’s been a completely different insight into that concerto. Mozart educated me at least as much as my parents. I think that his letters and way of thinking about the world, and his deep humanism, and the way he wrote to his wife and the husband he was—that was my complete romantic ideal. I think that all these rumors that his wife was not his match and not at his level of intelligence are so wrong. Constanze Mozart was actually from my hometown in the Black Forest. She looks like a typical Black Forest woman with her black curls. Mozart was another parent to me, he was another educator to me. For my first performance fee, I had a choice between receiving money or receiving the complete collection of Mozart’s works. To my mother’s dismay, I chose the collection, and I still have it at home: [Laughs] 20 volumes of his complete works. When I had the money, I bought all his letters—4,000.

HC: What sparked your interest in Mozart?

FS: It is the language. I think it’s the highest unity of form thought, the honesty and purity of soul and intelligence, the wittiness and humor, and being a world citizen. I think all of that is in his music, and it’s independent of the time. In his opera Così fan tutte, these women are not faithful, and it’s a big drama with all these husbands that are disappointed. And what is the motto of the opera? They say, “Yes, we failed. We cannot promise we can be faithful for our whole life, but we will try every day again.” Isn’t that wonderful? No student can promise to play a perfect concert, but you can try every day again. Isn’t that just a wonderful life motto? I believe it’s not about showing how perfect we are, but about integrating our difficult sides, and the failures we are going through, but always, everyday, to make it better.

HC: You’ve competed on that big international stage, and now here at IU, you have a lot of students who compete on that level. What role do you think competitions should play in a student’s education?

FS: In a good sense, they can be life-changing because you have to be ready at a certain time, you have to really be drawn to that repertoire, I find it very important that you love the repertoire because this is your life that will waste if you have no affinity for it. It is repertoire that will stay with you for a long time, so it needs to be good. I think the next USA [International Harp Competition] repertoire is one of the most outstanding [lists] I’ve ever seen. It can be life-changing when a student realizes, “I can do this,” with the time frame. Competitions give you a stage, and there are wonderful musicians listening to you who genuinely want you to do your best. There is no jury sitting there waiting for your mistakes; that’s the wrong image. I support competitions very much because this is what they meant to me. They’re also very important because you can lose, and it’s important to consider that the problem might not be that you lose, but that you win. As a winner, you can get stuck with the repertoire. Life doesn’t suddenly get easier, and it doesn’t mean that the phone is ringing every day. I think that we still have to fight for our instrument, for the recognition. I don’t think that you could do more than Susann McDonald did for the harp and for us all. And yet, still, there are so many preconceived notions about that harp, right? We have to fight. I think it’s important to learn to manage those hardships. I want to continue the work of Susann McDonald and dedicate my lifetime to getting the recognition and treatment we deserve.

HC: You have three young children—how has it been relocating your family to a new country, a new continent? That is a huge life change for them, as well as for you.

FS: I was very nervous about it—it’s actually our third move in a year. I asked my little son Eli (who is named after Elias Parish Alvars), “What do you think about moving again? It’s hard, isn’t it?” And he said, “Oh no, we’re used to it. We’ve had four moves by now.” I said, “Four? It’s only three.” He says, “No, no, the first one was from the clouds to your tummy.” And I said, “Oh, how was that move? Was it a difficult one or an easy one?” He answered, “We just needed a trumpet and a harp to take along.” [Laughs] And his twin brother Evariste said, “You know this is how we discover the world.” So with that confidence they displayed to me I thought, okay, we can do this. My children are the ones I learn most from, and I think I’m a very dedicated mom. I feel very fortunate—I didn’t plan on a family; all of them were beautiful surprises. I could have been without children, and it would have still been a very rich and full life, but I feel very fortunate that it all came together. Although, of course there are many nights without sleep. You learn so much and you learn how to surpass your limits when you didn’t even know you could. I am stronger for it. It also influences your music making—it is all one language. It is not two different lives. It helps me when I see female artists who have several children. Catherine Michel has five children, Marie-Pierre Langlamet has four, and Marielle Nordmann has three, and I’m sure there are many more. The fact that I had to figure out logistics with a harp helped me figure out the logistics of twins. Unfortunately harps never grow up—they remain difficult—but children grow up.

HC: You already touched on this subject, but for a student who comes to Bloomington to study with you for one year, or two years, or however long, what do you want them to leave this place with?

FS: I want them to have found their best voice. There is no single formula to say, okay, you cross these things off the list and then you have done it. I think you have to find out what you can do best. I hope I can help them do that, and maybe lead someone to go further when they are somewhat shy. It would never be my aim to have a similar type of student or anybody who copies me. On the contrary, it’s about that person. So my work is to really find out and understand how someone thinks and how someone progresses. I want them to accomplish a lot of repertoire here before they are on their own. You have to find out how to help them with practicing. It’s not about the hours we practice, it’s about how smart we practice. I want them to take risks and maybe even do it wrong, but do it with conviction, and then we talk about it. I want to help them become independent. I would say a teacher’s job is to disappear. That’s what György Sebők said when I was 22. He died soon after, but I remember how heart-breaking it was to hear that, because we didn’t want him to ever be out of our lives. But I understand now—you need to disappear so that somebody else can continue and teach others one day. •