Article extra

See our companion article Six Degrees for some sample trees of young professional harpists along with tips for how to build your own.

Who did you study with?” is often among the first questions we ask when we meet another harpist. Why does it matter? Connection. As social creatures, we want to feel connected, and asking about a harpist’s teacher is the first step in discovering the people and experiences we might have in common. What we may not realize is that we all have a teacher in common with almost every other harpist on the planet, if we go back in history far enough!

The harpists and teachers of the past are more than old names and black and white pictures in books. How we position our thumbs, play harmonics in both hands, and slide fingers for five-note passages, were once their new ideas. The harpists of the past influenced and changed the design of our instrument, from the mechanisms to the aesthetics. They composed many of the pieces we perform. When you play the music of Naderman, Bochsa, Hasselmans, Tournier, Grandjany, Renié, or Salzedo it is comforting, humbling, and mind-blowing to think about how they not only composed the piece, but also shaped the skills and interpretations of their students as they learned these works. Those students became teachers who in turn imparted the same knowledge to their students, and so forth, until the present day. Our collective harp knowledge today is the result of teachers passing along their skills, ideas, compositions, and innovations to their students over many generations.

Know Your Roots

Think history is only for musicology dissertations? Think again. We asked some of the harp teachers listed in these trees to tell us why understanding your harp heritage is important and relevant today. Read their comments

Tracing Your Tree

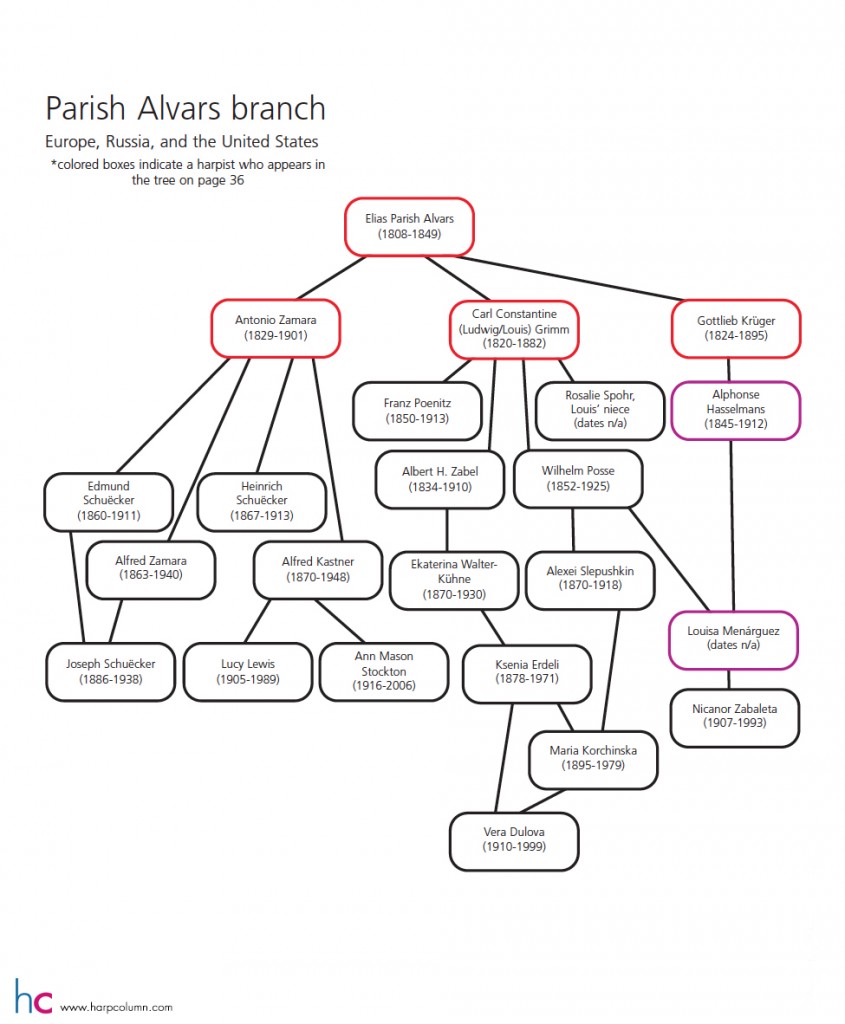

So where does your branch sit on the harp family tree? Start by looking at the trunk of the harp family tree with the harp’s founding fathers (first image, above). From there, we outlined the major branches of the tree. With a little research, you should be able to connect yourself to one of these branches. See the companion article Six Degrees for some sample trees of young professional harpists along with tips for how to build your own.

In order to figure out which branch yours grows from, start by asking your teacher about his or her teachers, which would be your harp “grandparents.” To figure out who taught your harp grandparents, start by asking your teacher if they know. If you hit a dead end, try looking online—many harpists list their principal teachers in their biographies. Roslyn Rensch’s book Harps and Harpists has a wealth of information about hundreds of influential harpists and the history of the instrument, from ancient times to the present day. Or check out Milton Govea’s book Nineteenth and Twentieth Century Harpists: A Bio-critical Sourcebook from the library. As you trace your line back through the generations, you will likely be able to connect yourself to a branch on one of the trees below.

Where’s my Family?

The family tree we’ve traced in this article has its limitations. Most harpists will be able to connect themselves to one of the branches we’ve outlined, unless you fall into one of these categories:

Self-taught: If you or your teacher were self-taught, just stick your branch in the tree nearest your biggest musical influences. Take a François Joseph Dizi for example. After teaching himself to play the harp as a young boy in Belgium, Dizi arrived in London in the late 1790s penniless, where he befriended Sébastien Érard who loaned him a harp. Dizi taught Elias Parish Alvars and became one of the leading harpists in London.

Celtic tradition: If you are a harpist from the Celtic harp tradition or study with a teacher from that tradition, you may not be able to place yourself on this tree. The Celtic family tree is much different and can be more difficult to trace than the classical pedal harp tree, given the Celtic aural tradition and its historically large number of self-taught musicians.

Non-Western harp heritage: If you or your teacher studied outside of the Western musical cultures (Asia, Africa, South America), then you might have difficulty placing yourself on this tree. For purposes of this article, we limited the genealogy to the major Western harp lines.

Once you know your history you can play “six degrees of separation” with famous harpists, like “Six Degrees of Kevin Bacon” for harp nerds! In fact, most harpists today are less than six degrees away from Hasselmans or one of his famous pupils. You may be surprised how few degrees of separation there are between you and all the other harpists out there! Hopefully when you look at the tree, you will see one big family of harpists with history, teachers, and a love of the harp in common. Keep the tree growing!

So who were our harp forefathers? Let’s take a look into our collective harp history at some of the important early members of our harp family tree.

The Hochbrucker Family

Jacob Hochbrucker (c.1673-1763) made harps in his workshop in Bavaria with five pedals connected via a mechanism to hooks or “crochets.” His five-pedal harps may have been the very first pedal harps, and from a harp with five pedals it was an easy leap for Hochbrucker and other manufacturers to create the single-action pedal harp with seven pedals. Jacob’s sons and nephews became distinguished harpists who promoted the new single-action pedal harp in concerts throughout Europe. Johann Baptiste Hochbrucker (1732-1812), son of Jacob, was the “premier harpiste” at the French court of Louis XV. Christian Hochbrucker (1733-c.1800), Johann’s cousin, was the “maitre de harpe de la reine” at the court of Louis XVI. Christian became a sought-after teacher and his students likely included Johann Baptiste Krumpholtz, Philippe-Jacques Meyer, Leonard Primovera, and Marie-Martin Marcel—the Vicomte de Marin. (Since there were many harpists in the Hochbrucker family, it is often difficult to be certain which Hochbrucker is referenced in historical sources.)

The Naderman Family

Probably the best-known harp manufacturer of the time, Jean-Henri Naderman (1735-1799) made single-action harps in Paris for the nobility and the French royal family. His sons François-Joseph Naderman (1781-1835) and Henri Naderman (1783-1842) succeeded their father in the family harp-making business. While Henri became more involved with harp manufacturing, François-Joseph studied with Krumpholtz and became one of the best-known harp virtuosos, teachers, and composers of his time. In 1825 François-Joseph became the first professor of harp at the Paris Conservatory, which would become the world’s epicenter for harp instruction. Some of F.J. Naderman’s students included Robert Nicholas Charles Bochsa, Théodore Labarre, Antoine Prumier, as well as both Jules and Félix Godefroid. Felix Godefroid became a great virtuoso (known as the “Paganini of the Harp”) and many of his compositions are still performed today.

The Cousineau Family, Erard, & The Journey from Single to Double Action

Though perhaps less famous, George Cousineau (1733-c.1799) and his son Jacques-George Cousineau (1760-1824) also made harps in Paris for the French royal family. Ever the innovators, the Cousineaus abandoned the use of the popular crochet (hook) mechanism and invented “béquilles.” This improved mechanism shortened the string by a half step using two béguilles, one turning clockwise and the other counter clockwise. They also created the first harp that could be tuned in C-flat and played in all keys, but it was not the double action harp we play today. This harp had literally two rows of pedals, 14 in all. Can you imagine? Fortunately for us, the French Revolution temporarily halted the Cousineaus’ harp production, and prevented the 14-pedal harp from tormenting future harpists.

Sébastien Erard (1752-1831), one of the Cousineaus’ competitors, fled the French Revolution to London, where he decided to find a way to double the action without using 14 pedals. Along the way to achieving this goal, he revolutionized harp design with innovations such as using several layers of wood for the neck, placing the mechanism below the neck (rather than encasing it in the neck), and replacing the béguilles with the two-pronged, forked disc called a “fourchette.” Eventually Erard patented the double-action seven-pedal harp in 1810.

Robert Nicholas Charles Bochsa (1789-1856)

Bochsa studied with both Marie-Martin Marcel–the Vicomte de Marin, a famous virtuoso of the day—and François-Joseph Naderman. Bochsa was the court harpist for both Napoleon Bonaparte and Louis XVIII before fleeing from France to England to avoid arrest on charges of forgery. He was appointed the first professor of harp at the newly founded Royal Academy of Music in London and toured extensively giving concerts throughout Europe, the United States, and even Australia. He composed a great deal of music and wrote instructional books where he argued the merits of sliding fingers (the 4th finger up and the thumb down) in five-note passages rather than using the fifth finger. Some of Bochsa’s famous pupils included Elias Parish Alvars, Théodore Labarre, and John Balsir Chatterton who later taught John Thomas.

The Prumier Family, Théodore Labarre & The Paris Conservatory

Antoine Prumier (1794-1868) began his harp studies first with his mother and then with F.J. Naderman. Upon Naderman’s death in 1835, Prumier became harp professor at the Paris Conservatory and, in a bold and welcomed move, replaced all the single-action harps with double-action harps at the school. Interestingly, both Antoine and his son Ange-Conrad-Antoine Prumier (1820-1884) are said to have played harp using all five fingers. Théodore Labarre (1805-1870) succeeded Antoine as professor of harp at the Paris Conservatory in 1867. In addition to studying with Naderman, Labarre studied harp with Cousineau and Bochsa, as well as composition with Boieldieu. Upon Labarre’s death in 1870, Ange-Conrad-Antoine Prumier, who had been teaching the conservatory preparatory classes, became the professor of harp. Among Prumier’s younger students was Alphonse Hasselmans.

Elias Parish Alvars (1808-1849)

A young three-year-old “Eli” Alvars first studied harp with his father, and later as a teenager, commuted from Devonshire to London for lessons with Bochsa. Alvars also studied with François Dizi and Théodore Labarre. Alvars developed a formidable technique and toured extensively throughout Europe as a harp virtuoso. He was among the first harpists to explore and exploit the double-action pedal harp’s enharmonic capabilities in his performances, arrangements, and compositions. Upon hearing Alvars perform in 1842 in Dresden, Hector Berlioz described him as “the Liszt of the harp.” Berlioz’s fascination with Alvars’ harp playing skills led Berlioz to become a great champion of the harp in his Grand traité d’instrumentation et d’orchestration written in 1843. Some of Alvars’ notable students included Gottlieb Krüger, Countess Esterhazy, and Carl Constantine Louis Grimm (also sometimes spelled Karl Konstantin Ludwig), who founded the “Berlin School” of harp playing.

Alphonse Hasselmans (1845-1912)

Born in Belgium, Alphonse Hasselmans studied harp with Gottlieb Krüger and Ange-Conrad-Antoine Prumier. Hasselmans was already a renowned soloist and orchestral harpist in Paris when he became professor of harp at the Paris Conservatory in 1884. An extremely demanding teacher, he remained at the Conservatory for 28 years where he was both revered and feared by his students. Hasselmans insisted his harp students play (as he did) with a rich and mellow tone achieved by using a hand position that included a straight thumb, finger tips placed so the fleshy part plucked the strings, and well-rounded hands with room for complete finger articulation closing across the palm. (Does that sound familiar?) Hasselmans composed only solo pieces, often with a specific pedagogical concept in mind, many of which remain part of our standard repertoire. His students became some of the most internationally famous harpists and teachers in history. The list reads like a parade of precocious stars including Henriette Renié, Enrico Tramonti, Marcel Tournier, Ada Sassoli, Carlos Salzedo, Micheline Kahn, Luisa Menárguez, Raphaël Martenot, Cecilia Praetorius (Morley), Marcel Grandjany, Pierre Jamet, and Lily Laskine.

Albert Henrich Zabel (1834-1910)

A pupil of Carl Constantine Grimm, Zabel was the solo harpist with the Berlin Opera before moving to St. Petersburg to be the harpist for the Imperial Russian Ballet. He published a Methode für Harfe in 1900 and composed many solo works that are still performed and recorded today. Zabel is credited with bringing the Berlin tradition of harp playing to Russia, and in 1862, joined the faculty of the newly founded St. Petersburg Conservatory. Among Zabel’s pupils was Ekaterina Walter-Kühne, who succeeded Zabel at the St. Petersburg Conservatory and taught Ksenia Erdeli.

Wilhelm Posse (1852-1925)

Posse received early musical training from his father and then taught himself to play the harp before studying with Grimm at the Kullak Academy in Berlin. He eventually became solo harpist with the Berlin Philharmonic and harpist to the Kaiser. According to Franz Liszt, who often consulted with Posse about the use of harp in his orchestral works, Posse was the “greatest harpist since Parish Alvars.” Posse was also one of the first harpists to choose a Lyon & Healy harp as his main performance instrument, in 1895. His harp solo compositions were popular with Alberto Salvi on his concerts in the early 20th century. Posse taught harp at the Royal Berlin Hochschule für Musik from 1890 to 1923. His students described Posse as strict, kind, and patient, and included Luisa Menárguez as well as Alexei Slepushkin, who taught Maria Korchinska.

Henriette Renié (1875-1956)

At the age of five, Renié saw a concert featuring Alphonse Hasselmans and famously declared, “That man is going to be my harp teacher.” She was not allowed to play harp until she was 8; even then she was so small her feet did not reach the pedals and she played using pedal extensions developed by her father. After winning her Premier Prix from the Paris Conservatory at the ripe old age of 11, Renié began teaching students, including a very young Marcel Grandjany. In 1901, she completed her Concerto in C Minor, becoming the first woman to publish a harp concerto, and that same year she also composed Légende. In addition to publishing many original compositions and transcriptions, she founded the first international harp contest in 1914. During World War II, Renié wrote her book, Méthode complète de harpe, at the request of Alphonse Leduc. After the war ended, students flocked to study with her from all over Europe and the United States. Renié’s students included Mildred Dilling, Marcel Grandjany, and Susann McDonald in the U.S., as well as Odette Le Dentu, Margerita Ciccognari (professor of harp at the Venice Conservatory), Odette de Montesquiou (author of Henriette Renié et la harpe translated to English as The Legend of Henriette Renié), Margeritta Michaelesco of Romania, and Emmy Hurlimann (professor of harp at the Conservatory of Zurich).

Marcel Tournier (1879-1951)

Marcel Tournier was born in Paris to a large musical family. His father was a luthier who required all his sons to play a stringed instrument, and eventually young Marcel enrolled at the Paris Conservatory at age 16 to study harp with Hasselmans. At the conservatory, Tournier discovered his love of composition and later won many composition competitions including the Rossini Prize and second place in the prestigious Prix de Rome in 1909. He supoorted himself through orchestral work and his position as harpist at the Paris Opera, and spent a great deal of time composing. His harp compositions are idiomatic to the instrument and loved by both performers and audiences alike. In 1912, Tournier succeeded Hasselmans on the faculty at the Paris Conservatory. Some of Tournier’s students included Jacqueline Borot, Gérard Devos, Elisabeth Fontan-Binoche, Marie-Claire Jamet, Lucille Johnson, Cecilia de Majo, Eileen Malone, Louise Came Pappoutsaki, Nicanor Zabaleta, and Bernard Zighera.

Carlos Salzedo (1885-1961)

Carlos Salzedo published his first piano composition at the age of 5. He began harp studies at the conservatory with Hasselmans when he was 13, and three years later he won the Premier Prix at the Paris Conservatory for both piano and harp on the very same day. In 1909, Salzedo came to the United States to become a member of the Metropolitan Opera Orchestra at the invitation of Arturo Toscanini. After serving in the French Army during World War I, Salzedo returned to live in the U.S. permanently and became the first professor of harp at the Curtis Institute. In 1931, harp students began coming to Maine in the summers for intense study with Salzedo, Lucile Lawrence, and eventually Alice Chalifoux at his Summer Harp Colony (also known as the Salzedo School). He was fascinated with the number five as evidenced both in the architecture of the Salzedo harp he designed with Witold Gordon for Lyon & Healy, as well as in the rhythms and meters of his compositions. His Modern Study of the Harp, published by G. Schirmer, Inc., explains many of his innovative harp effects and their notations that have intriguing names like aeolian rustling, falling hail effect, gushing chords, thunder effect, etc. His publisher also wanted Salzedo to write a method book, but Salzedo declined saying he preferred to spend his time composing and teaching. Lucille Lawrence felt so strongly he was making a mistake that she showed him an outline of her concept for a method book, and together Lawrence and Salzedo published Method for the Harp in 1929. Some of Salzedo’s notable pupils include Marietta Bitter (author of Pentacle: The Story of Carlos Salzedo and the Harp), Marjorie Call, Faith Carmen, Alice Chalifoux, Jeanne Chalifoux, Pearl Chertok, Reinhardt Elster, Velma Froude, Patricia John, Charles Kleinsteuber, Lucille Lawrence, Heidi Lehwalder, Lucy Lewis, Judy Loman, Marie Miller, Jude Mollenhauer, Dewey Owens (author of Carlos Salzedo from Aeolian to Thunder), Lynne Wainwright Palmer, Edna Phillips, Casper Reardon, and Marjorie Tyre Sykes.

Marcel Grandjany (1891-1975)

A musically gifted child, Marcel Grandjany received a scholarship to study with Henriette Renié when he was 9 years old. He later became a pupil of Hasselmans at the Paris Conservatory and was awarded the Premier Prix in harp at age 13. He returned to the Conservatory to study composition with Fauré’s assistant Jean Roger-Ducasse, and in 1913, Grandjany became a finalist in the Prix de Rome competition. He served in the French Army during World War I, and later worked as an organist and choirmaster in Paris. After the war, Grandjany toured extensively as a concert artist. Fearing the Nazi threat to peace in France, he moved to New York City and, in 1938, became head of the harp department at the Juilliard School where he taught until his death in 1975. Grandjany also established harp classes at the Conservatory in Montreal and the Manhattan School of Music. He felt strongly that teaching was a great responsibility. He often taught by playing examples, probably at first due to language barriers, yet it proved to be an efficient method and came to typify his style. After judging the first International Harp Competition in Israel, Grandjany was inspired to found the American Harp Society, which met for the first time on Dec. 3, 1962, in Grandjany’s New York City apartment. He composed many original solo and harp ensemble pieces and transcribed many works for harp that typically included careful fingerings and markings for placing and muffling. Some of Grandjany’s many noteworthy students include Anne Adams, Nancy Allen, Kathleen Bride, Sarah Bullen, Gretchen Van Hoesen, Ruth K. Inglefield (author of Marcel Grandjany: Concert Harpist, Composer and Teacher), Dorothy R. Knauss, Julia Hermann Edwards, Eileen Malone, Sally Maxwell, Lucien Thomson, and Jane Weidensaul.

Lily Laskine (1893-1988)

As an 8-year-old student, Lily Laskine was initially terrified of Hasselmans, but her mother, Dora, insisted she continue her lessons. She studied privately for three years with Hasselmans and then spent two years at the Paris Conservatory where she was still so intimidated that she never came to lessons alone. It may have been a desire to spend as little time as possible with Hasselmans that motivated Laskine to earn the Premier Prix at the age of 13, and thus no longer be eligible for lessons. She began teaching at 14, and became the first female orchestra member of the Paris Opéra in 1909. In the 1930s, she made several European concert tours and began a recording career. In addition to recording classical albums as a soloist and with flutist Jean-Pierre Rampal, she can also be heard on popular recordings with Edith Piaf and Maurice Chevalier as well as on film scores. She advised her students to say yes to every possible opportunity to perform, reasoning it would broaden the instrument’s exposure, improve the student’s performance skills, and raise the chances of future employment for all harpists. When Tournier retired in 1948, Laskine and Pierre Jamet became professors at the Paris Conservatory. Some of Laskine’s students include Barbara Allen, Jane Allen, Nancy Allen, Caroline Leonardelli, and Susann McDonald.

Pierre Jamet (1893-1991)

Pierre Jamet’s mother worked as a pianist for the House of Pleyel. Through her contacts there, the Jamet family learned Pleyel was looking for young musicians to promote the chromatic harp. Young Pierre auditioned and won a chromatic harp, free lessons, and entered the chromatic harp class with Mme. Spencer at the Paris Conservatory. When Hasselmans heard Jamet’s jury, he was so impressed he advised the Jamet family not to waste their son’s hard work on an instrument that he felt would soon be obsolete. Hasselmans must have made a pretty convincing argument because Mme. Jamet left her position at Pleyel, and Pierre began lessons with Hasselmans privately and free of charge on an Erard double-action pedal harp. At 16, Jamet entered the Conservatory again and in 1912 received his Premier Prix. Hasselmans’ warning about the demise of the chromatic harp would eventually prove correct, but in the early 20th century some composers were still not sure which instrument would prevail. The Debussy Sonate for Flute, Viola, and Harp was first premiered on the chromatic harp, but in 1916 Debussy wanted to hear it performed on the Erard double-action pedal harp and asked Pierre Jamet over to his home to perform the work. Debussy was suitably impressed and asked the trio to perform it for several concerts he was organizing. Thus, Jamet became the first harpist to perform the sontata on a pedal harp. Both Jamet and Laskine became professors of harp at the Paris Conservatory when Tournier retired in 1948. Some of Pierre Jamet’s students include his daughter Marie-Claire Jamet, Catherine Michel, Bernard Galais, Martine Géliot, Marie-Madeleine Bouchaud, Brigitte Sylvestre, Annie Fontaine, Catherine Eisenhoffer, Yvette Colignon, Annie Lavoisier, Arielle Valibouse, Susanna Mildonian, Anna-Maria Loro, Ruth K. Inglefield, Carl Swanson, Ernestine Stoop, Maria Graff, Setsuko Shimazaki, and Annette Gôl. •

Know Your Roots

We asked some of the harp teachers listed in the historical trees above to tell us why understanding your harp heritage is important and relevant today.

In my opinion, those students who have the opportunity to study with teachers from different ‘branches’ of the tree and to delve deeply into the nuances of differing techniques have a strong advantage in today’s world. They are able to develop a wonderful synthesis of tone and technique. Students who study with teachers from multiple schools of playing may have a broader perspective and more tools. The flip side is that many students in today’s mobile society don’t have the opportunity to ‘go deep’ and may not be able to fully assimilate one style of playing before moving to another. This can result in a lack of understanding of why a particular technique might be used in any given situation.

—Delaine Fedson Leonard

Regarding the question of ‘belonging’ to a harp family, I like the idea of being part of the French harp family or maybe should I say ‘French harp tradition in music,’ as one of its main focuses is sound and colors, things of great importance to me. But on another hand, I am happy that now harpists are opening up to more harp families and traditions. I think that it is very important for us to learn from the others, outside our ‘family.’ It also makes us think a little more independently about what is there, what we want, and what is important for us, musically speaking. This opening gives us choices [where]as before we were more inclined to do what we were told.

—Isabelle Moretti

There are many styles of music and in my experience, no one technique or approach to playing fits all of them. After achieving a solid foundation, I believe students gain scope and perspective by working with people from different traditions. After all, the goal of playing an instrument is to play ‘music.’ Technique is merely a tool to help accomplish that goal.

—Stephanie Curcio

Knowing the origin of my technical choices gives me context; context to make interpretive choices in my playing and context to help guide discovery in my own students. For me these are fundamental requirements for the art of making music: knowing what has come before, what influences shaped the music we are playing, and how others—particularly the composer/originator of the music—understood our instrument, and what would make it sound the most beautiful.

—Lynne Aspnes

I think it is to young harpists’ advantage that they are able to study with several teachers from different “branches” of the tree. In doing so, the students have a chance to learn different aspects of their playing through different styles of teaching and observations. However, it is important to keep in mind that music is a subjective art, and one teacher may have a different opinion from another. Therefore, keeping an open mind and taking notes of what each teacher suggests is extremely important.

—Jessica Zhou

In my education I studied Grandjany, Salzedo, Renié (through McDonald) and Russian techniques (through Korchinska). I have found it invaluable to have many options to offer students according to their needs, and to have them respect the vast amount of knowledge that is available.

—Carrol McLaughlin

Don’t forget to check out our companion article Six Degrees for examples of harp family trees in action.