—by Elizabeth Jaxon

My journey to Brest to meet Nikolaz Cadoret took me first through the major European capital of Paris, as all roads in France do. But as the train moved away from the city and plunged deeper into the countryside, the terrain took on its own unique quality. The city of Brest can be found all the way at the far-western tip of France, where the land reaches out into the Celtic sea. It lies within the cultural region of Brittany, the traditional homeland of the Bretons—one of the six Celtic nations. Most people associate the term “Celtic” with the British Isles to the north, because the Celts also made their home in Cornwall, Wales, Scotland, Ireland, and the Isle of Man, but one pocket of this ancient culture survives across the channel to the south, here in France.

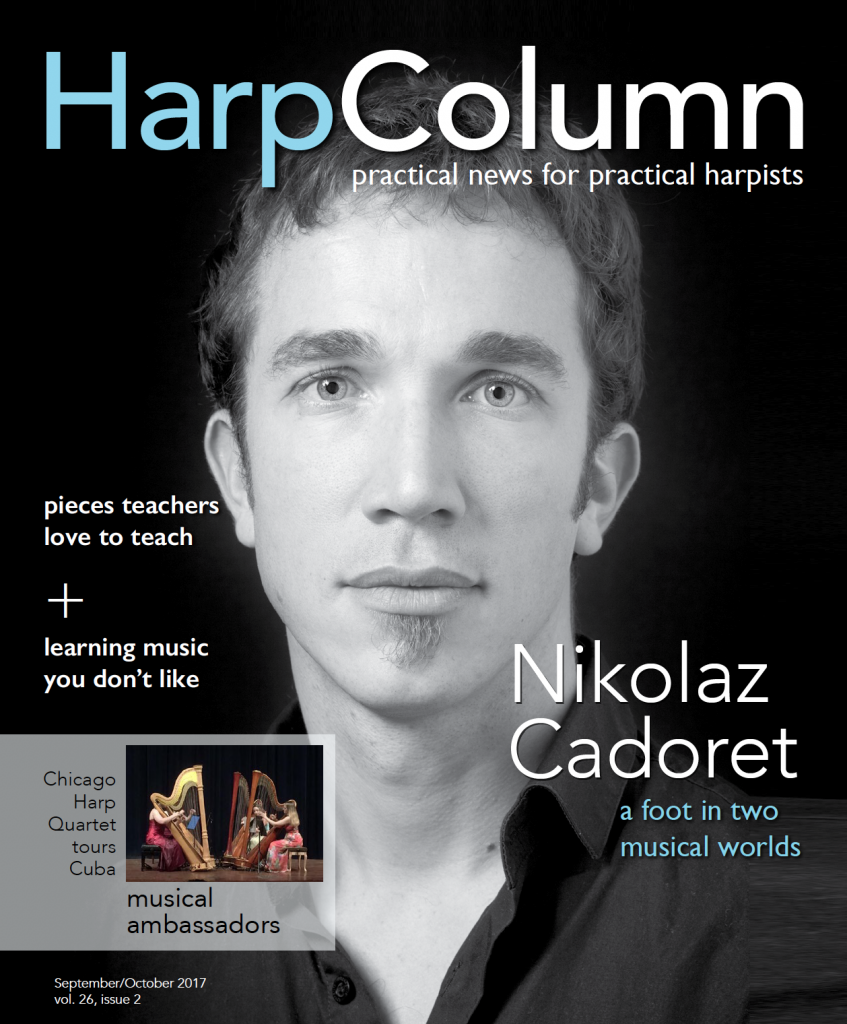

Growing up within this Celtic culture, Cadoret’s first experiences with music were a mix of styles. He began his studies with Dominig Bouchaud who not only introduced him to traditional Breton music but also to classical music. The diversity in his early music education gave him a well-balanced foundation from which to explore many different genres. He went on to play in traditional music bands as well as the Berlin Comic Opera, and in 2004, he took home one of the top prizes from the USA International Harp Competition. Today, he is a multifaceted harpist, excelling in not only traditional and classical music, but also incorporating jazz and improvisation to create a style that is uniquely his own.

Harp Column: Here in Brittany, there is a strong Celtic music traditional. I’m curious how this Celtic music culture that you grew up in has influenced you. How did you get started with the harp?

Nikolaz Cadoret: Actually, I never dreamed of playing the harp. I just wanted to do music—that was for sure. I really didn’t know which instrument. I began with one year of solfège lessons at the music school in Quimper, and when it came time to choose an instrument, the school organized a concert for the pupils as a way of introducing us to all the instruments. I was with my father, and first there was a performance of the “Pink Panther” on a trombone. “Wow!” I said. “I want to play the trombone!” But my father told me, “Just wait a bit until you’ve heard the rest of the instruments.” I don’t remember the exact order, but then there was a guitar, and that also sounded very cool and made strange sounds. And I said, “Okay, I want to play the guitar.” Next came the harp—very cool as well. I was like, “Wow, that’s nice!” But my father asked the teacher, who was then and still is the teacher in Quimper, Dominig Bouchaud, “How can you cope with so many strings? It seems so complicated.” Dominig Bouchaud told my father, “Put your son on stage, and he will see for himself.” So, I went on stage. It was probably a very small stage—I don’t remember the way it was exactly—but for me it was like Carnegie Hall. Dominig Bouchaud just put the harp on my shoulder, and I don’t think I even plucked a string, but I saw the light coming through the strings. That was my first contact with a real musical instrument. After that, I just knew I wanted to play the harp. That was it, without even playing. I really have no memory of the sound. It’s quite important, this beginning, because I didn’t see the harp as a fantasy or a dream or anything. For me, the harp is just a medium, really. It happened that I began the harp, that I play the harp; it worked between me and the harp. That’s it.

HC: So, you’re saying that it could have happened differently. It could have been the trombone, for instance.

NC: Exactly, or percussion, or anything, I don’t know. But back to your question about the Celtic influence. At the time when I started the harp, in the late ’80s, Dominig Bouchaud was not yet focused only on Celtic music. His background was on the classical pedal harp, and it was a period of transition for him, in his pedagogy. He was actually teaching a very classical technique—a strong, powerful technique, but classical. We worked on a bit of classical music, a bit of Celtic music as well, notes, a bit of learning by ear, so it was not only Celtic at the very beginning. But of course I was playing on a Celtic harp. It was not the huge instrument, not frightening at all, and also not expensive, at the beginning.

HC: Okay, so you were exposed to both traditions together, from the beginning.

NC: Absolutely. In the beginning, I played small minuets by Mozart, pieces by Grandjany, Hasselmans… Then after the first few years, the focus shifted more and more toward traditional music. You’re right when you say there is a strong tradition here. When I was already still quite young, I had the opportunity to play Celtic harp in Fest Noz. Fest Noz is a term in the local Breton language referring to a traditional music festival where you have live musicians playing and a lot of people dancing traditional dances. It’s something really, really lively. During summer, you can find these kinds of concerts every evening all over Brittany, and during winter maybe every weekend. There are a lot of bands and musicians, and it’s a very, very strong tradition. Very soon, very early, I had this opportunity to play the harp in a very functional way. You know, this dancing function of the music. That was quite important.

At the same time, there was always classical music. Dominig Bouchaud was very keen on getting his pupils to play a large range of musical styles. So I had classical technique, I could read music as well, but I could also learn by ear, and I knew how to arrange very simple dance melodies. Both styles of learning were fundamental in my development as a harpist.

HC: Often, young students tend to prefer one or the other—note reading or learning by ear. How did you combine the two?

NC: It comes from the repertoire. When I was studying a classical piece, it was by reading, but if I was studying a traditional piece, it was by ear, with no notes at all. This balance was quite efficient. You know, classical music without notes… It works for a bit, but quite soon you have to get back to the notes. But traditional music I can learn by ear.

With my students, I try to mix all the time. I find I can use oral pedagogy in classical music when they encounter things they can’t read. Some things are just too complicated, or they didn’t yet learn certain notes or a certain kind of rhythm. I tell them, “It’s simpler than you think. I’ll play it for you.” And when I do, they say, “Ah, ok!”

Another way I combine the two, which Dominig taught me how to do, is that I learn something by ear and then I write it. That’s a good technique. For example, if you have a gigue with dotted rhythm, dotted rhythm is something you learn how to read and write quite late, but it’s actually quite simple to reproduce and to understand. So I tell my students, “You know this rhythm that sounds like this? Well, here’s how you write it.” That way, they see a direct link, and they don’t forget it. That’s how I combine both things. It worked well when I was learning, and with my students now it’s also working well. Otherwise, when you approach music only through what’s written, the problem is you only play what you can read. [Hums quarter notes and eighth notes.] That can be cool when you’re 6 or 7, but it can quickly become boring. It’s a pity. With oral learning, you can play things you can’t read, and you can also play faster. It’s really something I believe in, this pedagogical mix—a specific pedagogy for a specific repertoire, for a specific musical culture, for jazz music as well. Dominig Bouchaud was not really into jazz music, so he couldn’t teach me the harmonies, but with my students I do jazz or pop music. Even very young students understand right away what C major is, what C minor is, and they can play it right away. I don’t talk about voicings, I just write “C” and then I say, “Only the C is written, but maybe you can play a C and a G or a C and an E.” And then when they understand what a chord is, you can build their harmonic consciousness, which is very useful for harpists when they get into classical music and moving pedals.

I really believe in this mix. At least for the first five years, mix everything! This place where I started the harp, in Brittany, where there’s this strong Celtic tradition was I guess a perfect ground for this. I was exposed to both oral tradition and written tradition. It was very useful.

HC: How long did you study with Dominig?

NC: Quite long actually—10 years. From age 7 to 17.

HC: You mentioned that after you began with this pedagogical mix, you then got even more into Celtic traditional music. What happened that led you more into Celtic music?

NC: I went deeper into Celtic music starting from around age 14 or 15. I was actually interested in playing with rock bands, but at that time there were not so many electric harps. It was hard, because there were no examples. You wouldn’t necessarily think to use the harp in a rock band. But at that time, I was in love with Nirvana—that kind of stuff. So I bought some scores of their music, and I tried to play it on the harp, but Dominig couldn’t help me. On the harp, I found it so complicated, so I started the guitar. As far as harp goes, though, it was much easier to play Celtic music in bands. So when I was 14 or 15, I started to play in traditional bands, amplified as well. That was also the beginning of my exploring effects and amplification stuff. I learned how it worked through my experience with my electric guitar and effects pedals, so then I started experimenting with my harp.

HC: When did you start playing the pedal harp?

NC: Actually, around the age of 17 or 18, I decided not to be a professional musician. That was actually not my goal. I thought, well, music is cool, but it’s always been a hobby. I should mention that in Brittany, traditional music is much more important than classical music, and in traditional music—it’s less and less true now, but at that time—there were not so many professional musicians. Everybody was doing it as a hobby, even if they were playing at a professional level. It’s part of the tradition to go out playing every night, concerts or Fez Nos, and to work during the day. Playing music as a very strong hobby was normal.

So, I decided to begin literature studies and political studies. And when I was about 19, I was invited to the harp festival Arles, to play Celtic harp. And at that festival in Arles, believe it or not, was the first time I saw the pedal harp. Really! In Brittany, pedal harp is something rare. It was taught in Brest, Lorient, or Rennes, and at that time that was it. So in Quimper, no pedal harp. I barely knew what it was. But in Arles, I saw people my age playing classical pedal harp, and I was very impressed by all the possibilities you get with the pedals and all the classical repertoire you can play. I also saw how hard they worked and how seriously they took their music studies. And I thought, well maybe I made the wrong choice, maybe music is my thing. When I came back from Arles, I told my parents, “It was great, but maybe a bit too great. Maybe I will switch my studies to classical pedal harp.” And they followed me. They said, “Okay, we will support you, as long as you do it in the proper way.” So I rented a pedal harp, and I spent seven hours a day practicing—I barely attended classes at the university anymore. That was when I was 20. I worked like hell. It was so amazing because it was a new instrument with so many possibilities. I had originally wanted to play jazz on the pedal harp, but then I discovered all the classical repertoire. I thought, well, maybe classical repertoire is a good start, just to build your technique. Thanks to Dominig, I had a very strong classical technique, so it was not complicated.

I first started with some small Naderman etudes, a bit of Grandjany, Jane Weidensaul—but then I wanted to play Bach’s Goldberg Variations. So when I got into the Rennes conservatoire with Evelyne Gaspard, who was my first teacher on pedal harp, I played the Aria and a few variations from the Goldberg Variations. My repertoire didn’t take a normal progression. After those first few pieces, I got right into Bach and Caplet. There was kind of a gap there! Thanks to Dominig I already had the right technique, you know, and it was such a marvel to discover all this repertoire. I initially thought I would just dip my finger into classical music but then I was swallowed by it. It was fantastic! That’s why afterward I got more and more into classical music. Evelyne Gaspard didn’t like romantic repertoire, so I played more contemporary, modern stuff: Caplet, Holliger, Debussy, Ravel.

After only about one-and-a-half years with Evelyne Gaspard, I then entered the Zurich Hochschule with Catherine Michel. I was with Catherine Michel for four years, and she was actually the teacher who took me deeper into the technique that’s useful for romantic, virtuosic music, like Parish Alvars. I loved it, but whew, it’s a lot of work!

HC: That’s all the more impressive to know that you had only been playing the classical pedal harp for a few years when you became a semifinalist at the USA International Harp Competition in 2004.

NC: Yes, that was in 2004, the year Emmanuel Ceysson won. And after that, I started doing orchestra auditions. I went from Zurich to Aachen, and then to Berlin. In Aachen I played in the symphony orchestra. That was my first job. And then I went to the Komische Oper Berlin (Berlin Comic Opera). I did the Verbier festival and extra playing in different orchestras in between as well. I also studied with Xavier de Maistre in Hamburg, preparing orchestra auditions. He taught me how to win an audition. He knows how to do that, right?

Xavier de Maistre was an incredible coach. He helped me get the job in Berlin. I was doing auditions all over Europe, and even in Toronto. Xavier was the one who really did the right coaching. I remember my first lesson with him, when I was still living in Zurich. I went to Hamburg, and I was preparing an audition for the Konzerthaus orchestra in Berlin. It was two weeks before, and I was not ready. When I arrived in Hamburg, after a very short night of sleep, he told me, “You’re lucky today! All my students are either sick or couldn’t come, so we have the whole day for our lesson.” It was an eight-hour lesson, and it was exhausting. But, wow! The guy is an incredible musician, but also a machine. He can teach four hours in a row without a break, working only on orchestral excerpts. Two hours on Tzigane. It was just what I needed. He has such a strong energy. That’s how I finally got my first job in Aachen and then in Berlin. Great, great, great experience.

At the same time, I was still playing a bit of Celtic music, but I had to take a break. Not because I didn’t like it anymore, but just to learn all that I had to learn in classical music. It’s a lot of work, and very fast. I didn’t have this long, calm progression you normally have, because I started later than usual. I had a lot to learn and a lot of very complicated repertoire to learn. So I put aside the Celtic music for a few years, but at the same time, I was developing a very strong practice of improvisation—jazz improvisation and free improvisation.

HC: Was improvisation something that you were doing on your own, without any guidance from your teachers?

NC: Yes.

HC: What led you to jazz?

NC: Very simply, that was the music I was listening to. I had friends who were also playing jazz and doing free improvisation as well. A very good friend of mine—Pierre Starck—played the saxophone, not as a professional, but with him I formed my first free-improv duo. I just jumped into improvising and put a lot of jazz flavor into it as well as contemporary effects. Then I also leared a lot playing along with Jérémie Mignotte, a fantastic jazz flute player, in our contemporary jazz duet, Meteoros. As in traditional music, jazz gives you a great amount of freedom with the instrument. Because you know, in traditional music, you learn a very simple melody, and then all the variations, the arrangements, and everything come from you. Most of the time it’s improvised. So, I already had a very free relationship with my instrument. For me, it was simple and natural.

HC: Why did you leave the orchestra in Berlin? What happened?

NC: I didn’t really quit. In Germany, you have a trial period, and at the end of my trial period, I didn’t get the contract. In Germany, it’s just very, very hard. You may get into an orchestra—great—but then you have a one or two-year trial period, and the average success rate is only 50 percent.

HC: How long was your trial period?

NC: My trial period was one year, but I started playing there almost a year before my official contract began. I spent almost two years there in total. It was the best education ever. Especially because, in the Comic Opera, we played both opera and symphonic music. We were playing so much; in one week, we might play five different operas, have rehearsals for the next operas, and then rehearse in the morning and afternoon for a symphonic concert that evening.

HC: It sounds like you crammed many more years of experience into just those two years that you played with the Berlin Comic Opera.

NC: Yes, it was a very strong education for rhythm. It also taught me to play more boldly. When you have to play, you play. You don’t discuss. No, you play, and you have to play it right.

Looking back, though, I think I was much too involved in each concert. When you play five concerts a week, you can’t play each concert as if it was the last. When you play solo recitals or chamber music, you have to really put yourself into it. When you play in orchestra, you can’t play like this. You have to be more removed, laid back.

Anyway, in the end, I was not confirmed in the position. Obviously, it’s a professional problem—losing your job is a bit awkward—but it was not sad. At that point, I had been playing with very strong professional orchestras for about five years, and I realized it was not really my thing. After my contract ended, I could have tried to do other auditions, but I didn’t. Because actually working in an orchestra was not my thing. It was a lot of work, and I loved the orchestra, it was a great experience, but I didn’t like it enough to go on. There was the complicated alchemy of micro-societies within the orchestra “family.” There was a lack of artistic freedom. And there was a sense of “going to work.” I couldn’t cope with this. You know, it’s like when you play a solo classical career, you have to be made for this. I can’t play a solo classical career. I tried it. I did a few recitals. It was great, but I realized I’m not made for this.

HC: You just have to be honest with yourself.

NC: Exactly, I’m made for playing my music. That’s my thing—playing my music on stage, or traditional music with small formations. And yes, I guess I also need artistic control, even if I can share the artistic control with my colleagues.

HC: How would you describe your music?

NC: I’m still looking for a definition of my personal style. During my time in Berlin, there was this question of how to make the link between classical, jazz, improvisation, and pop music—you know, all the styles of music I studied or played during my years of learning. How can I mix them together?

HC: How can you make it your own?

NC: Yeah, exactly, and that’s still a question today. I don’t know. I do a lot of different things, and I find it fascinating to jump from style to style. It depends on the project. I have a chamber music ensemble where we play written music, but my Descofar trio is more open, with traditional music as our starting point. We play on electric harp, with percussion, and we put a lot of improvisation into what we do. A few things are written, but we might have a solo part in the middle, for example, and you never know how many cycles it will last. If the audience is still hot, you can do not four but eight or 24, or just play on cue, improvising together. But when I play my music, it’s a mix. You can hear the strong Celtic roots in my music—there’s a modal quality that’s always there. Without traditional music, I always feel something is lacking, which is why I came back to it in 2010. But I don’t play clean. I guess what I’m looking for is something very sensitive, but energetic as well, with a lot of strength—sometimes too much, I admit—I want something a bit savage, wild. Because it’s something you have also in traditional music, this kind of wildness, something raw.

HC: Something you don’t quite get in classical music.

NC: Yeah, because in classical music you try to have it very polished and controlled. Once you’ve got that, you can maybe take some risks. In my music I also work a lot on control, but I like it when the music dares to go out of the boundaries. That’s why I also like free improvisation and rock ’n’ roll, this kind of borderline music. I guess I would say that’s my style.

HC: What brought you to Brest?

NC: I was not actually planning to go back to Brittany. But there was a position open in the Brest Conservatory, and when I read the description, I realized it was made for me. They were looking for a teacher who was able to teach classical harp, Celtic harp in the traditional way, and who was also interested in developing electric harp in the pop or rock music field.

HC: There’s not a lot of harpists who fit that category!

NC: Yeah, and it’s Brest. I was born here. I also already had connections in Brittany. I had been traveling and working all over Europe, and it was a good moment to go back to my roots. It’s great—here in Brest, I have such freedom in my teaching. I feel really supported by the conservatory. Teaching here doesn’t feel like just a way to earn money. It’s a place where everyone is connected, and the teachers are considered as artists. We have strong connections with the whole musical scene of Brittany, of France, and even the world. The conservatory even has connections with jazz musicians and labels in Chicago and New York. Since I came back to Brittany, I have never played so much as when I was living in Berlin, or in Paris after that. There are so many opportunities here. I play not only in Brittany but all over Europe, and soon I’m coming to the States. You know, when you are in the right place and you do the right things, everything becomes simpler. Suddenly everything is right. I’ve reached that point in my life, and in my music—everything is simpler.

HC: Regarding your teaching philosophy, what would you say is the most important thing that you hope your students learn from you?

NC: It’s a bit cliché, but passion. Passion and joy to play. That’s the most important thing. Because, you know, not all of my students are aiming for professional careers in music. I do have about four or five each year who want to be professional (and there are more and more people pursuing traditional music professionally these days), but the other students I have are just here to learn music. What I want most of all is to see my students on stage with a big smile and playing music. If you don’t have this kind of joy and passion and interest in what you play, you can’t play music. Music involves technique, of course, but above all, you have to express yourself through the music. Even if they have their fingers in the wrong position, with their thumbs under their second fingers, passion is the first thing.

After that, flexibility or, as we say in French, souplesse, is very important—flexibility in style and also in technique. As I said, in the first five years, students should get experience with as many different music styles as possible, but also with different techniques. They have to stay flexible and soft because, you know, there is not just one technique. I have some students coming from other music schools who arrive with very strong classical technique, for instance. That’s perfect, it’s very helpful, but when they want to play Irish music, something very fast, it’s not working. You have to change things. You can’t play very fast Irish music with a classical hand position. So if your hands stay flexible, soft, and strong enough, you can always correct things later. Children won’t understand why they need to keep their thumbs up if they have no problem playing. At a certain point, after maybe two or three years, they will understand why, but before, you remind them and they just forget. As long as they’re flexible it’s okay, but if their hands are too rigid they won’t be able to change. So I encourage flexibility in style, technique, and mind.

HC: You mentioned some of the ensembles that you are currently playing with, and your website lists several more. What other projects are working on right now?

NC: Yes, I don’t even know how many there are—it’s a lot! Of course, not all of them are active at once; some of them are on hold. Right at the moment, today on the 20th of July, I’m working on a project about the harpist Kristen Noguès, with Collectif ARP. Collectif ARP is an association of five harpists—myself, Clotilde Trouillaud, Cristine Mérienne, Alice Soria-Cadoret, and Tristan Le Govic—who decided to work together and to roll in the same direction to find concerts, to find programs, to take care of administrative work, and get the communication together. I guess you could call it a label or a production company.

HC: That’s really interesting! Those things can take a lot of time, so I can definitely see the advantage to teaming up with other harpists. So you support each other’s careers, even if you’re all doing different things?

NC: Yes, we don’t handle all of the communication, but we do maintain a global network for the five of us. We organize workshops and summer courses. We also produce recordings. We all work together, communicating on behalf of each other’s careers, and it’s quite efficient. Now in addition, we’re also working on a common project centered around Kristen Noguès—a harpist from Brest, who died 10 years ago. She was a solo harp player who also worked with very important musicians in the jazz and traditional fields. Tristan le Govic is working with Jacques Pellen, who was the last companion of Kristen Noguès (and a jazz guitar player himself), to put together notes and scores of her music. Jacques Pellen was there when she was composing her music, so he knows how it works. She created so much, but she never really wrote down her music, and sometimes she would just play with no score at all. So we are doing the work of piecing together and publishing her work.

We’re also making new arrangements of her music. Together with Jacques Pellen, as artistic director, we’ve put together a performance involving five harps: three acoustic harps, one electro-acoustic harp, and one electric harp. Because you know, Kristen Noguès worked with Camac to develop the first electric harp, back in the ’80s. Of course, the first serious attempt to make an electric harp was by Salvi, but it was not a completely electric harp. Then in 1982 or 83, Camac built the first fully-developed electric harp, with Piezo pick-ups. So we’re playing the show this summer in various festivals, but for now it’s really just a concert. Next year, starting from January 2018, we hope, it’s going to be a bigger show with staging and lighting as well as more music. We are also going to record an album of her music. Actually, two albums: one of the scores we are going to publish (which has more of a pedagogical purpose), and one of the music we’re going to play in the show.

That’s my main project at the moment, but another project that I am developing at the moment is my Descofar trio.

HC: Your Descofar trio is also something which you do together with your wife—Alice Soria-Cadoret—is that right?

NC: Yes, my wife also plays the harp, so we have a lot of projects together actually.

HC: I’m curious about that. It’s quite rare to meet two harpists who are a married couple. Where did you two meet?

NC: We met on a small tour organized by Catherine Michel, right before [the USA International Harp Competition in] Bloomington. Alice was coming back from Philadelphia, where she had been studying with Judy Loman at the Curtis Institute of Music. She was also a former student of Catherine Michel, so when Catherine Michel was organizing this small tour for her students, Alice joined us. Then she came to Zurich to do a master’s degree with Catherine Michel at the same time that I was also studying there.

HC: And you don’t find that you’re too competitive with each other?

NC: Well, we used to be, a bit. It used to be a bit complicated when we were both doing orchestra auditions. That’s never funny when you do the same competition or the same audition. No, it was not easy all the time, but right from the beginning, we decided to do some duets together. And now we are doing this Descofar trio with Yvon Molard, and we are both members of the Collectif ARP as well. Alice also plays the electric harp, and we have a rock band named JeanJeanne. We are playing a lot together, and it works!

HC: That certainly sounds better than competing for one position.

NC: Exactly. We also have a chamber music ensemble called the Ensemble 8611, which is more classical music, with a flute player, Nicolas N’Haux, and a singer, Joanna Malewski. We both play the harp in Ensemble 8611, but it’s acoustic harp, and Alice is on the pedal harp. I play a bit of pedal harp as well as Celtic harp, and our repertoire is a mix of written, classical music and traditional music played in a classical way.

HC: It sounds like she’s really creative and has a similarly open-minded approach to music.

NC: Yes, yes! We don’t play the same way, but she also really likes exploring. She used to play a lot of young-audience shows. She has produced contemporary music for musical theatre. She played in cabarets in Germany. So, she’s into many different styles. She says that when she was studying in America, she noticed that the musicians there were more open to exploring and combining different styles with no real boundaries. They didn’t have any problem making the transition from an orchestra concert in the evening to a late-night gig in a jazz club afterward. No problem! She says, all of this is music after all. Why do we care about keeping the styles separate? You know, in France, sometimes people have this kind of attitude. They say, “You play classical music very well, but we know that you come from traditional music, and we can feel it in your playing.” A lot of people told me this when I first started playing pedal harp. When people found out that I came from a traditional music background, they would say, “Oh, but you can hear it. You have a very strong pulse, but sometimes maybe you lack a bit of…” You know. It also can work the other way too. People say, “We know you’re a classical musician, and we can hear it when you play jazz.” It’s just, you play what you play, and you probably have a dominant style, because you can’t excel in everything, but you can be really good in one thing and then be not so bad in others. I find it great to be able to play many different styles. You just have to know your limits. I know I’m not a classical soloist. I don’t pretend to play solo recitals on the pedal harp, and that’s fine, but I can play chamber music, and I hope not so bad. I just love to have a mix. It’s all music, after all.

HC: You and your wife just had your first baby—a daughter. That must be an amazing feeling. What’s it like for you to be a father?

NC: Well, it’s tiring! And it’s great! Like I said before, when you are in the right place at the right moment in your life, things are very simple and natural. It’s also not like I’m suddenly someone different. It’s a lot of learning. And I have to learn very fast, because my daughter learns faster than I do! The time is incredibly full. She started out as such a small thing, and after one month, she already smiles. Suddenly you have a smile, and every day it’s different. It makes me realize how slow we get when we grow up. No, really, children are so flexible at this young age. Something which really stunned me was one of her first sleeping moments. When she was asleep, in the very first days, it was incredible to see how quiet she was. It was a sleep free of all problems, a completely innocent sleep—wow. No worries, no problems, just deep and peaceful sleep, a moment of perfect balance. We lose that so quickly, and then we try our whole lives to find such peace again. But you have it right away, from the beginning. It’s marvelous. People can tell you what to expect when you become a father, but there’s nothing like discovering it yourself for the first time. You know, when things are going wrong [in other areas of my life], I just think to myself, “Okay, but I have a daughter, so it’s not so bad, it’s not so important.”

HC: I imagine you’ve learned a lot about life just from having a daughter, but do you think it’s affected your music at all?

NC: I don’t know yet. It’s only been one month. What I know is that I don’t have so much time left to practice. I’m realizing that, even when I have to play, and I don’t have time to practice, I can play without practicing.

I don’t know if it has changed my music, but I did have an interesting experience at a performance recently. On the 4th of July in Paris, I played a project with Hélène Breschand called FackZeDirtyCut, which is a free improvisation duet. We play harp and we also recite and sing texts. For this last performance, Hélène wrote a new text that she wanted me to read while playing. The text was “Je suis la femme” (“I am the woman”), and it was a long text, written in a powerful style, about being a woman, a mother, a lover, and giving life. But I was saying all this as a man! I guess she wanted there to be distance between the speaker and the words—a shifted lighting on the text. So there I was, on stage in front of an audience, improvising at the same time, and I didn’t have time to think too much about it. But I realize that, as a father, those words meant much more to me. Suddenly it’s not theoretical, it’s not philosophy, it’s reality, it’s life. Of course, I didn’t actually give birth myself, but I was there, and I felt like, “Wow, now I know what this is really about.” I would say intensity brings meaning to life, for me. Having a baby brings more meaning to life and gives me a different perspective on life. You see this small thing learning so much, having so many difficulties just to grow up, just to gain half a centimeter, and she has this capacity to marvel about things. It’s so intense. I’m sure it will change my music, but not right away. We can do another interview in a year, and I’ll tell you. For now, I’m just trying to survive!

HC: You’re going to be traveling America soon, in November, for the Camac festival in Washington D.C. The festival program features you presenting a workshop and performing in the final concert. What can people expect from your workshop?

NC: I plan to work on traditional music, most likely using an oral learning method. We don’t have so much time, however, so I may also hand out some written music in advance, so that people will at least have the melody. I hope the workshop will be a discovery of Celtic music and specifically of Breton music. I’ll be bringing along a bit of my tradition from Brittany and also a bit of my own style. We will see how, with a very simple pattern and a melody, we can go anywhere—with arrangement, improvisation, variation, and mixing cultural aesthetics—independent from whatever technical level you are at. It’s very important to realize that you don’t have to wait to be very good with your instrument to play music. Even if you can only play two notes with two fingers, you can still play some crazy stuff, and it will fit. I hope to leave the participants with a large toolbox. In my workshops, it’s very rare that I aim toward a finished product. It’s not the kind of workshop where you learn the melody, bass, and chords all in one hour and then go home with a new piece in your repertoire. That’s very rare. You will probably have the feeling afterward that you’re not sure exactly what to play, but you have a huge toolbox which can keep you busy—for years, I hope.

HC: Will you bring tunes from Brittany? I’m sure American harpists will not necessarily be familiar with those.

NC: Yes, most of the time I bring songs from Brittany, which are traditionally sung or played by older instruments like the biniou (bagpipes). They can sound very strange and exotic to someone who has never heard that kind of music. Even sometimes for people from Paris, when they hear it, they are shocked. They say, “That’s the music you like?” It’s sometimes very wild, sometimes very subtle. So, I will present these songs in my workshop, but I will also tell the participants, “Don’t lose what you have. You have your own personality, you have your own cultural background, so use it. Use your technique, optimize everything you have, and put your own creativity into it.” I believe traditional music is the best place to express your creativity. It’s very flexible, malleable. You have rules, of course, but you don’t have to play in the most traditional way (which will take you alive). You can also decide just to use it as inspirational material and take it in your own direction. I’m going to explain how I play, offer a few techniques, and show how to arrange a melody in just a few minutes. You may not realize what you can do in such a short time. I encountered this quite a few times in workshops with classically-taught harpists, who often don’t feel confident enough to say, “I can do it!” They are taught that they have to practice a lot to play their music, which is quite complicated technically. Playing exactly what’s written in the score is one thing, and it’s very important, but it’s just a small step to switch on the confidence it takes to dive in right away and just do it, with very simple tools. Afterward, you’ll see it helps your classical music as well. It helps a lot to have this kind of “I can do it” attitude.

HC: After your workshop, then, you’ll be doing the final concert with three different youth harp ensembles. What will you be playing with them?

NC: Good question! We are going to play traditional songs from Celtic countries, not necessarily Brittany. In this case, because we won’t have a lot of time, I’m almost certainly going to send scores. But they will be simple scores. Then, when I arrive, we have rehearsals together, and maybe we will play around with the structure and change it a bit, and I will play with them. I hope we can do it that way, so I can play along. I will see. It’s a great adventure. America is an adventure country! We’ll see when I get there.

HC: Will this be your first time in America?

NC: It will be my first time playing in America, apart from Bloomington and some vacation. Otherwise, I’ve never played in America before. I’m looking forward to it! •