—by Lynne Abbey-Lee

When I was at the University of Michigan, one afternoon during a lesson my teacher, Ruth Dean Clark, announced the date of our next studio recital. “Oh, a friend and I just got tickets for Chicago for that night,” I replied, referring to the band famous for “Color My World”and many other ’70s pop hits. “What are they playing?” asked my teacher, assuming I meant the Chicago Symphony Orchestra. Needless to say, I dashed to the concert after playing in the studio recital.

This anecdote illustrates the attitude many teachers used to have about popular music: It wasn’t even on their radar. As a teacher, I am much more accepting of pop music than my teacher was. Some of my students may occasionally even think I’m cool when I assign songs they know from current culture. But I can’t begin to compare with the hipness of the teachers you’ll read about later in this article. They don’t just toss a token pop piece at their students here and there. They take an entire genre that many of us dismiss and find tangible assets they can add to their teaching resources, using it to instruct or reinforce musical concepts. I’ve only recently given more thought to the wide-reaching power of pop in my teaching, and my students are already reaping the benefits. Let’s take a look at a few case studies.

Inspiring Early Readers

Students Speak

Ask nearly any harp student what music they listen to at home and the answer will have three letters: P-O-P. Bringing their familiar music into their lessons is a win-win for students and teachers. Jump to the end to read what students had to say about the benefits of pop.

Brenna, a 9-year-old, is still learning to read notes and rhythms. Figuring out a new piece can be time-consuming, and she may lose interest. When she first asked about playing “Tomorrow” from Annie, I thought it might be too advanced for her, but her enthusiasm for a song she loves has propelled her forward. After taking on “Tomorrow,” she is playing hands together more than before, changing levers during a piece, and playing rhythms that she’s not yet able to read, but can play by ear. I’ll also play it for her while she follows the music, so she can better relate what she hears to what she sees on the printed page.

A high-school beginner is having a similar experience with “Our Song” by Taylor Swift. Knowing how it should sound helps her have more confidence that she is playing correctly than she would have with an unfamiliar piece. The familiarity of pop music for both of these students helps their confidence as their music reading skills grow.

Discovering Independence

Last year, Morgan, an eighth-grader, really wanted to learn “Stairway to Heaven” by Led Zeppelin, her dad’s favorite song. Rather than use one of the harp arrangements available, she chose a version from musicnotes.com because it was closer to the original. Learning this song without all of the harp idiosyncrasies figured out for her provided Morgan with rhythmic challenges, good lever-flipping practice, decisions to make about phrasing, and new ways to think about muffling, all of which advanced her playing for any repertoire.

Karisa is a fan of Animal Crossing: New Leaf, a video game I’d never heard of. She has always done a good job of picking out songs by ear as well as composing, but is not confident about reading complicated rhythms. She wanted me to hear a song from the game, and after I did, an assignment was born. The song features various creative rhythms, including ties, syncopation, and sixteenth-note triplets, over a steady eighth-note pattern. Karisa’s mission was to write out those rhythms, approximating as best she could anything she didn’t understand. Tricky counting became more than a theory exercise.

Exploring Ensembles

Four of my lever harp students who play as an ensemble are working on “Say Something” by Great Big World. (To see a one-page sample, go to www.musicnotes.com, search for “Say Something,” and click on the second offering, for “Easy Piano.”) In this one song, there is a wealth of material to improve rhythm, phrasing, theory, and ensemble skills. I have them working in unison, with the objective of encouraging careful counting and listening to each other so that the sound is truly cohesive. They can also play the song as a solo, as fifth-grader Brianna did for her school talent show recently.

With a time signature of 12/8, there has been ample opportunity to talk about counting the “little beats” and feeling the “big beats,” even swaying with the dotted quarter note to feel it physically as well as conceptually. Brianna and Karisa, a seventh-grader in the group, have been working on the same rhythmic concept in Variation III of Bernard Andrès’ La Gimblette.

I’ve urged students to “sing the phrase” countless times in their music, but it becomes all the more real in the first page of “Say Something,” which alternates between single measures of melody and accompaniment and has them thinking about how to make that distinction. Later on, when the left-hand accompaniment jumps into the treble clef, their job is to remember to keep it from intruding on the melody.

Pop singers generally don’t sing in strict rhythm—neither does any opera singer I’ve ever heard—and the printed rhythmic notation can be different than what is on the recording. The ensemble made a decision to stick with the printed rhythm when playing in unison in order to stay together, but when playing solo, they might mimic the singer’s liberties, or take their own.

The chord structure of the piece is a recurring pattern of half measures each of B minor, G major, D major, and A major. Sometimes we’ll repeat a verse and give two of the four a chance to improvise on those chords. In 12/8 time, sure, it’s easy to play 3-note arpeggios in each hand, but asking, “What are some other things you can think of to do with those chords?” leads to all sorts of possibilities, some that sound great and others that might not make the cut.

Slowing down together to end the piece provides additional work on ensemble skills, this time visual rather than aural. I want them to do it without a conductor, so watching the leader’s hands (whoever it may be for a particular rehearsal) to place the last several notes at just the right time is a new skill for the group.

The same ensemble recently started Matt Mayberry’s arrangement of “Clocks” by Coldplay. I use this arrangement for gigs, and when lever harp student Brianna brought it to me as a solo request, she had the pedal-harp version in hand. At the time, I was unaware that Mayberry has also written a lever version in one sharp instead of four flats. But maybe that was for the best because Brianna had recently come to understand the magic of key signatures, which allowed for a lesson on how a piece in four flats can work on a lever harp tuned in E-flat by raising everything a half-step to three sharps and continuing to read the printed page. The only pedal changes in the original, from G-natural to G-flat and back, become lever changes of G-sharp to G-natural and back. After looking at the tune with fresh eyes, I decided that it would also be a great song for the group.

“Clocks” extensively uses the rhythmic pattern shown in example 1 (opposite page), along with other right-hand rhythms on top of the left-hand pattern shown. The right hand fingering is 12312312, which is also one way of counting the left-hand rhythm. I want each student to be able to play this pattern near the beginning of the piece in measures 5–12, with both hands, just as an accomplishment in itself. After that, in order to make it a group piece that will come together quickly, they split into parts, playing either the right or left hand. When their part is the right-hand rhythm from the example, I have them alternate measures between right and left hand to emphasize consistent tone quality and seamless alternating of the hands. The left hand part from the example can be broken up easily into left hand on the downbeat and right hand playing the rest of the measure.

The Hook

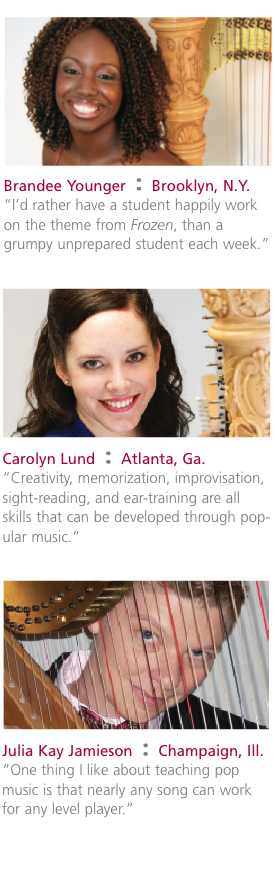

All of the concepts I’ve been able to explore with my students through pop music can also be taught and illustrated using standard classical repertoire. However, not every student stays as interested or motivated on a strictly classical music diet. Julia Kay Jamieson is a harpist, teacher, and composer living in Champaign, Ill. “The common thread with all my students who like popular music is that they are looking for a way to connect their harp life with their everyday life,” she notes. After a previously unmotivated student requested some Beatles tunes, Jamieson delivered. The student began to practice more and started a rock band with some friends, giving her a “doorway to creativity and social fun,” as Jamieson puts it. Some tunes that have “cheesy and obvious expression” can help students open up musically.

Carolyn Lund, Artistic Director of the Urban Youth Harp Ensemble (UYHE) in Atlanta, agrees, and goes further. “The average student that I teach is not familiar with classical music at all. Pop music is a way to grab and keep their interest, and an essential tool when I am trying to teach them to play by ear. I remember learning Für Elise on the piano as a child. I knew how to read music, but because I had heard that song hundreds of times, the notes combined with what I knew it should sound like enabled me to learn it quickly. The students I teach do not have that same aural familiarity I had with classical music. So if I want them to have that experience where they line up the notes on the page to a melody or rhythm they have heard a hundred times, I have no choice but to use pop music.”

Brandee Younger is a multi-genre performing and recording harpist and teacher in the New York City area. She noticed an unmotivated student posting movie soundtracks and photos of pop singers on social media, and realized that the student wasn’t into her harp music. A new pop song made things better for both teacher and student, “I’d rather have a student happily work on the theme from Frozen, than a grumpy, unprepared student each week.” Younger also points out that improvising was the norm for musicians of the Baroque era, and it is remains an important skill to foster in today’s students.

Pop music has always been a part of these harp teachers’ musical vocabulary. All three teachers listened to popular music growing up, attended concerts, and played tunes on the harp with their teachers’ blessings. Lund started learning pop music when she began to play gigs in high school, using arrangements of standard love songs from the ’60s, ’70s, and ’80s. Younger’s teacher transcribed songs she requested. “I even nervously played a Stevie Wonder song for an AHS evaluation one year and Dulcie Barlow was the adjudicator. She loved it!” Younger recalls. Other artists in her repertoire as a student included Barbra Streisand, Babyface, Toni Braxton, Robert Maxwell, The Carpenters, and Whitney Houston.

“Often I would play popular music by ear and just use it for goof-off time,” says Jamieson, fondly recalling songs such as “Take Five,” “Rock Around the Clock,” and “Yellow Submarine,” which she arranged in harp ensemble.

It Doesn’t All Work

Since pop song choices tend to be student-driven, it’s important for teachers to provide guidance about what might not work as well on the harp. “Quick duds,” says Jamieson, “are the ones where the melody depends on the words to be interesting.” She’s also found that a lot of chromaticism can be daunting to a beginner or on lever harp, or an arrangement can be too busy and confusing and momentum is lost while trying to make it playable. After Lund worked out an arrangement of “Dynamite” by Taio Cruz for her UYHE students, they found the many repeated notes in the bass became exhausting to play. Rather than discard it, they changed the character of the song by slowing down and eliminating notes to make it fun and keep it in their catalog. The accidentals and left hand in “Once Upon a Dream” by Lana Del Rey deterred a lever student of Younger’s, and the two decided to walk away from it. Younger acknowledges, “Students understand that the song won’t sound exactly the way they hear it on the radio, but they like it to be close!”

Real Pop

Each teacher has her own way to make songs work for her students. When a song has repeated notes or long half notes, Younger likes to create an arpeggio pattern. Arpeggios might seem mundane when presented to a student in an etude. But playing that pattern while bringing out the melody becomes anything but mundane because that melody is a favorite tune. Arpeggio practice is re-invented, and an arrangement begins to take shape. In another instance, a fingering pattern that gives a student trouble in classical pieces is conquered when she tackles the same pattern in Margot Krimmel’s arrangement of “Walking in the Air” from The Snowman. Younger notes, “Tricky rhythms are also great to teach because the student knows the melody by ear, so we can clap the rhythm while reading it, and make syncopation a bit easier to understand.”

“One thing I like about teaching pop music is that nearly any song can work for any level player,” says Jamieson. Having an early beginner play whole notes on the downbeat while she plays the melody teaches ensemble skills and provides enjoyment in being part of something they selected together. Depending on ability, she suggests that a student could play the root of the chord in a half note, quarter note, quarter note pattern in a song like Meghan Trainor’s “All About That Bass,” or arpeggiate the chord for each measure, and even play along with the recording. “It’s like playing with a super-fun metronome,” she notes. At another level, a student could figure out the melody and write it out, then tackle the rhythmic notation. More advanced students might play melody and simple chords, using sheet music, a lead sheet, or their ears to figure out what works. Delving into a Christian pop tune with a student led to discussions on voicing, chord progressions, changes to make the arrangement more harp-friendly, and expression.

Lund listens to a lot of pop music on the radio while thinking about what would work well on the harp, going to piano sheet music to start an arrangement. She wants her arrangements to look as professional as standard classical music, and hopes that her students will regard both genres with the same degree of seriousness. Even with the freedom pop music provides, she requires her students to play a song accurately as written to start, then opens it up to improvisation, spending time experimenting with chords. To teach theory, she chooses pop over classical because the chord symbols are built in and are usually straightforward. The skills built from reading chord symbols can then be applied to classical or other styles of music. Lund’s arrangement of “Halo” by Beyoncé was successful with her students and their audiences, and includes lots of syncopation, quick repeated notes, and many layers, all of which improved rhythm proficiency. Michael Jackson’s “Beat It” was another favorite and required a lot of listening to replicate how he accented certain words. She says, “It taught my students how to have better control of their individual fingers. If everyone’s accents were in the same place the ensemble stayed together, even without a conductor.”

Go Pop

So if you are a teacher thinking, “This all sounds good, but I don’t know what the kids are listening to these days,” Jamieson urges, “Try it, have fun with it, and think of it as continuing education.” It’s an ideal teaching tool to motivate students, encourage expressive playing, and challenge them to master difficult rhythms. Younger adds, “I feel it makes for a more well-rounded musician, to be able to thrive in more than just a traditional setting.” Lund lobbies for teaching classical and pop concurrently, “Creativity, memorization, improvisation, sight-reading, and ear-training are all skills that can be developed through popular music,” she says.

“No matter what the genre, rhythm, pulse, technique, tone quality, and expression are universal,” says Jamieson. “I know that if a student is learning something well, they are building and growing and on their way to somewhere worth going.” •

Students Speak

Jayla Thrash: “I think it’s important to play pop music because classical music is more appealing to older people, and pop music is more appealing to kids our own age. We might inspire other kids to play the harp by playing songs they like to listen to.”

Julia Blackwell: “With classical music, there are a whole bunch of dynamics you need to follow. With pop music, you can experiment and change it up. You don’t have to play it a specific way for it to be considered right. It teaches us to have more freedom of expression.”

Henry Cox: “Pop music has a lot of really fast and complicated rhythms, so it definitely forces you to improve your technique.”

Nia Anderson: “It’s good to be versatile. If you’re sticking to one genre, you’re not going to have as many opportunities. Pop music reaches a much larger audience than classical music does.”

Skyla Budd: “Sight reading pop tunes is a good start to practice sight reading. You know what it is supposed to sound like and [it] makes the task fun.”

Brianna Kay: “It helps me progress because it is easier to know what to fix when you know the music. It encourages me to try to improve on a song. It is less frustrating when you know how and where you need to improve.”

Sofe Cote: “Playing pop music allows me to expand my musical repertoire in new and interesting ways. It also helps me figure out how to transpose music better, which is a useful skill.”

Laura Mest: “I think playing pop music gives more opportunity for improvising and creativity. It helped me to think outside the box and create my own piece with other musicians, which was much different from what was on the page.”

Emily Contos: “It helps me progress because I need to think about how to use the colors of the harp in a way to make a piece sound pop-ish. Playing pop music on the harp allows me to explore sound and technique in a new way.”

Amanda Krueger: “Playing pop music has allowed me to accelerate the initial stages of learning a piece. Because [the song] is already familiar to me before I sit down to play, intellectual bandwidth is freed up so one can spend energy on the areas of playing that require improving.”