Behind every twirling snowflake and pirouetting flower on stage in Tchaikovsky’s iconic Nutcracker ballet are the flying fingers of a harpist. Sometimes, if we are lucky, two harpists.

The music is what we all dream of—a gorgeous, exposed part with big juicy rolled chords, arpeggios that fall beautifully into our hands, and even our own cadenza. But our dreams quickly turn to nightmares in spots where the part is awkwardly written or we are scrambling to cover two parts on a single harp.

The Nutcracker is tough to crack on your own, but with some advice and edits from our experts, you will have the benefit of wisdom gained from over 1,000 performances behind you. So pull out your score, sharpen your pencil, and get your part ready for the upcoming Nutcracker season.

Big Picture

I must have played the Nutcracker about 300 times, with six years in the National Ballet of Canada Orchestra, then the Vancouver Symphony Orchestra accompanying the Goh, Alberta, Pacific Northwest, Kirov, and Royal Winnipeg Ballet companies.

Two Harps are Better than One

Lucky enough to perform Nutcracker with two harpists? Check out our tips for playing the part as originally conceived by Tchaikovsky, including the markings Natalia Shamayeva uses with the Bloshoi Ballet.

There are varying repeats and tempos among ballet companies, so always work from their parts, but keep your own copy for fingerings and pedals. Don’t take metronome markings too literally; dancers take their own tempos, and the conductor follows them. The rehearsal letters are often in illogical places, so put in lots of cues and split the multi-rests into phrases.

The harp represents the magical elements of the story, so it should sound sparkly, elegant, and slightly spooky. But above all, it must be rigorously rhythmic and in time.

“Much of the score is playable as written but all tempos are subject to each ballet company and its choreographer,” notes Pacific Northwest Ballet principal harpist John Carrington. “Tempos can vary several notches on the metronome, making a passage unplayable as written—the opening of the Waltz of the Snowflakes, the opening of Act II, and the Final Apotheosis all come to mind.”

Orchestra pits can have notoriously bad acoustics, so it is essential to keep an eye on the conductor, and to be hyper-aware of what the other instruments are doing when you are playing. Listen to the whole ballet, and get all your cues marked in before your first rehearsal. You can check the score (free online at imslp.org) for additional cues.

Essential Edits

More Markings

Want to dig in further? John Carrington recommends the following published edits of the Nutcracker part:

“The Nutcracker Ballet,” edited by Kathy Bundock Moore (combination of harp I and harp II), published by Harps Nouveau.

“Tchaikovsky Orchestral Studies,” published by Lyra Music Company. “This contains his three ballet parts, the Zabel version of the cadenzas (Zabel was the harpist who premiered Tchaikovsky ballet works), and a combined Harp I and II part for the final pas de Deux.”

Editing the Nutcracker Ballet is essential, especially if you have to reduce the part from two harps to one. So let’s go through the score scene by scene from the beginning to highlight edits that will make your part playable. If you’ve been playing the part for years, some of these observations and tips will be obvious, but there are also some brilliant editing nuggets that you will want to add to your score.

Act 1, Scene 1: Be aware that the glissandi still have the F-sharp in them, even though there are naturals and flats in the other notes.

Scene 6: Change A-flat in the 15th bar, change F-sharp and D-sharp (enharmonic E-flat) in the second half of the bar before A. At rehearsal C, I omit the first F in the upward arpeggio, so that I am sure to get the top D-flat in time. Six bars after rehearsal K, the glockenspiel covers it, so split the top line between the hands. It becomes more exposed at the end of the passage.

Scene 8, Pas de Deux: This works well as written, and the two parts combine easily.

Scene 9, Waltz of the Snowflakes: These are evil snowflakes, and the part can be equally evil to play. The harp is essential to maintaining the rhythm, so you must keep the baton squarely in your sights. For that reason, in the 12th bar of A, I omit the lowest B, and place everything in advance (see example 1). If you play the C-flat instead of the B in the next bar with the left-hand thumb, you can place it early without causing a collision. Willy Postma, former harpist of the Trondheim Symphony Orchestra in Norway, agrees that dropping notes for the sake of being rhythmically clear and strong can be the way to go here. “The [Waltz of the] Snowflakes is difficult to play in sixths, sometimes it helps to play only the top notes, but it depends on how big the orchestra is.”

Carrington also focuses on the top line in the arpeggios after rehearsal A. “For Snowflakes I will often only play the top line of the e-minor arpeggio and add the sixth on the downbeat of the next bar,” he says.

Before rehearsal D, practice counting and feeling the rhythm—every alternate bar you are on the first beat, so be absolutely rock-solid on it.

At F, the two parts criss-cross, so combining them means that each eighth note is an interval of a third (see example 2). The orchestration is thick there, and a choir should be singing (sometimes this is substituted with a MIDI keyboard). You get a glorious solo glissando at I, so play both harp parts (glissandi in contrary motion) and enjoy your big moment!

At K, things can fall apart, so memorize that part and keep your eye on the conductor. Carrington suggests playing this by combining both hands into thirds and then alternating hands as necessary. The part gets tiring at M, so split the top line between the hands.

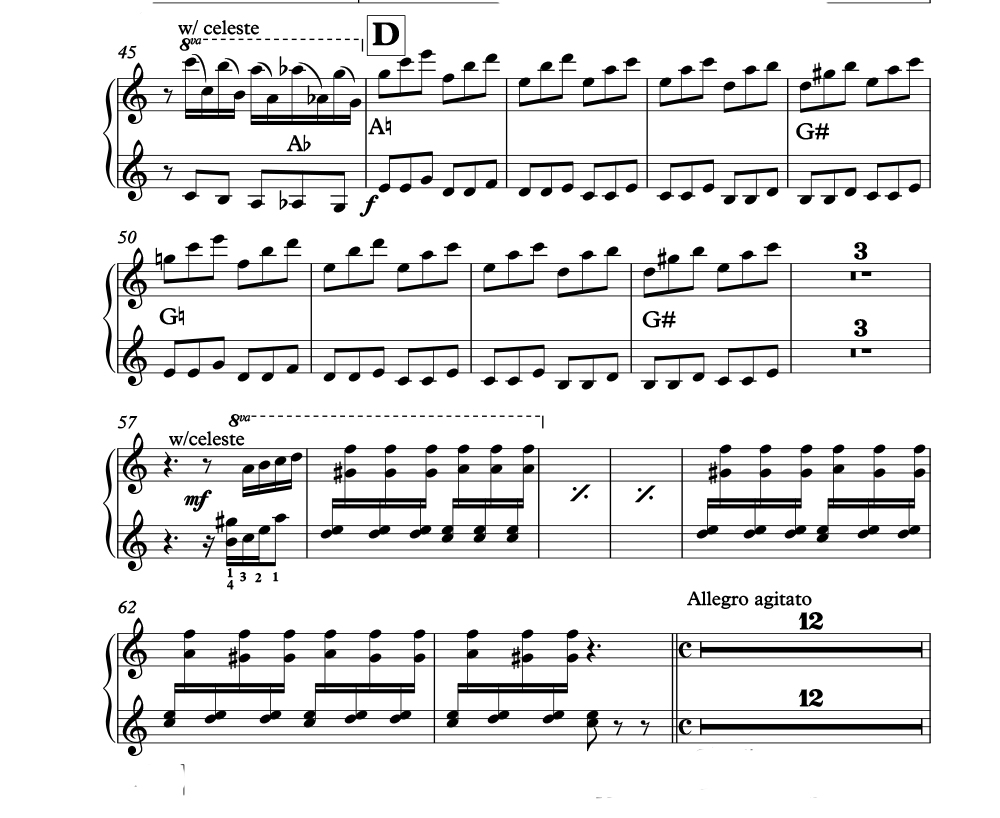

Act II, Scene 10: The curtain opens and there is wild applause as the audience takes in the scenery. This can make it tricky to hear the orchestra, so keep an eagle eye on the baton. This scene is a marathon of challenges for the harp. Judy Loman taught me the enharmonic re-spellings and the brilliant fingerings that you see in example 3. Two bars before A is a notoriously difficult spot. At rehearsal C, the two harp parts are combined and written with some enharmonics that make it sound smoother and easier to learn as well.

“This gives many a headache,” says Postma of the notorious excerpt two bars before letter A. She plays chords in the same harmony as the written excerpt, but changes the top note to the melody and plays it with the right-hand thumb on the eighth-note beat.. So the right-hand thumb would play F-F-F-F-F-F, A-A-A-B-B-B, D-D-F-F-A-B, D-F-etc., just as she has written on top of the bars here. You can see her personal markings for the excerpt in example 4.

“Once, when I performed this with two harps, I had a conductor pull me aside and ask me to point out to the second harpist that she was playing in the wrong octave during the second page of Act II,” says Carrington. “He was so accustomed to hearing it played by one harp that when he heard the left hand bass part he thought she was wrong!”

Scene 11, Clara and the Nutcracker Prince: In the section before rehearsal C, play the second harp part if there is only one harpist (see example 5). Postma agrees, “I do play both parts—it isn’t difficult—but you should know it almost by heart. From B, many harpists only play a triad in the top, but it is possible to play everything correctly as written. I would push the harp a little away with my knee so that I have more space at the top.” The celeste plays with the harp through that segment. Then at D, play the top line of the first part and the bottom line of the second. Re-finger the part as shown in bars 57–63 of example 5.

Waltz of the Flowers: There is a long wait before the famous cadenza, while the character dances play out. About two minutes before your entry, start wiggling your fingers to warm them up and do some deep breathing to oxygenate your muscles. Keep in mind that the cadenza is depicting the entrance of flowers, so don’t make it sound like the ballerinas are coming in on a wrecking ball.

Natalia Shamayeva, now retired from the Bolshoi Ballet, tells the story of how the Bolshoi’s then-principal harpist, Albert Zabel, showed Tchaikovsky how much better the cadenza sounded with the right hand playing before the left hand instead of simultaneously, and a glissando toward the end of the cadenza, instead of the double arpeggio towards the end. Tchaikovsky loved it, but never went back to the printer to get it amended. Interesting food for thought as you decide how to edit your part.

Everyone has their own take on the cadenza. “I resist making it a quick technical exercise of arpeggios and chords,” says Carrington. “This is the solo dance for the lead flower and my approach is to treat it like a perpetual unfolding of a flower’s bloom cycle, much as we see in a time-lapse film of a flower blooming. My teacher Lynne Palmer liked to start off the main section of the cadenza with an added sixth-octave A for resonance. Sarah Bullen also recommends this. Try it, you’ll like it!

“I sing the melody that the horns announced in the opening measures with my right thumb as I alternate the rise and fall of the arpeggios with one bar of crescendo and one bar of diminuendo for the first four bars, with some breathing and rubato, then gradually accelerate and crescendo to the top. I take my time on the descent and gradually make up for the rubato at the top by accelerating to the bottom. Things get a little cloudy with overtones down there so it works to speed through that. After a fermata at the top of the arpeggio, I play the rolled chords with some strength and leisure (as it is marked ritard) and play the final three chords each successively quieter with a broader roll—like a flower slowly opening its petals.”

To gliss in place of the double arpeggio, I move the F-pedal into natural in bar 23 (when I play the top B), then put the F and D pedals into flat position a bar later, to avoid the pedal noise that might result if you wait until the gliss (see example 6). In the waltz, after E, I substitute E-flats for D-sharps, and I use a B-sharp instead of C in the second bar of the second ending before letter K.

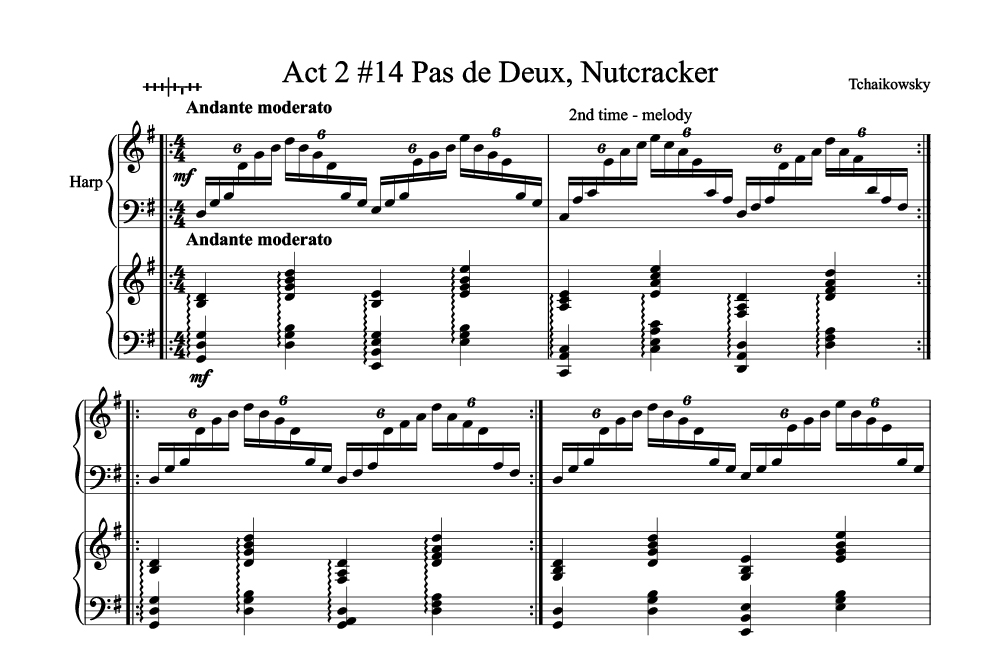

Scene 14, Pas de Deux: I used to add some of the chords from the second harp part, but it necessitated crossing back and forth with my left hand. This made it difficult to keep my eyes on the conductor, so now I only play the first harp part. The timing is more important than anything. Postma is a proponent of adding the chords from the second harp. “I play all the notes in the first six bars in my right hand and the chords from second harp in my left hand (see example 7). From there, I play the bass notes from second harp, so you’re not missing much. But all chords should be written in the harp part. This needs concentration and memorization,” Postma says.

In the section beginning at seven bars before B, I use four fingers of the right hand for the middle notes, and jump over it with three fingers of the left hand. Two bars before B, I slightly alter the voicing of the arpeggio to make it smoother (see example 8).

Six bars before C at the incalzando can be very fast, so I break up the top line between the hands, though still adding some harmony (see example 9).

Scene 15, Valse Finale and Apotheosis: The end is near, but the harp’s work isn’t finished quite yet. After D, the celeste doubles the harp, so you can play just the top line, splitting it between the hands (see example 10). It is possible to play both lines, but it can go very fast, so it is good to have this plan B. Carrington agrees. “I often have to resort to leaving out the left hand and dividing the right between hands for the quick tempo our PNB production takes. The celeste doubles what is missing.”

At F, play the top line only. At K, I play it like the cadenza (see example 11), with right hand followed by left hand, instead of simultaneously.

Whether you are gearing up for your first or 50th Nutcracker this year, working in these edits now will have you dancing through your part just like the dancers on stage come December. •