- Kosako performs with his trio of Daryl van Druff on drums and Bill Douglass on bass.

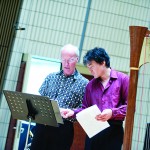

- Kosako performs regularly with musicians around Sacramento, including Paul McCandless on English horn.

- Kosako admits that music isn’t everything to him. “In the big picture, I think I am using music as one of many activities to make myself a better person, both spiritually and physically.”

- Motoshi’s cat tries to lend a paw as he does some work on his harp.

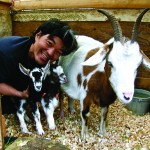

- Kosako, pictured with his goats, raises many animals on his land in the Sierra foothills of Northern California.

- Kosako believes there are many similarities between playing an instrument and martial arts. He holds a second-degree black belt in Judo.

- Motoshi Kosako talks over some music with Paul McCandless. Kosako has collaborated with the multi-instrumentalist on two albums.

The peaceful countryside of California’s Sierra foothills couldn’t be further from the bustling, electric cacophony of Tokyo, yet these are the two places jazz harpist Motoshi Kosako calls home. Motoshi grew up in Tokyo, one of the world’s most densely populated cities. Yet he always dreamed of living some place simpler. So in the late ‘90s he moved across the ocean, though it might as well have been a world away, to the serene Sierra foothills a couple hours outside of Sacramento. Chirping birds replaced blaring car horns as the loudest sound in Motoshi’s landscape.

Motoshi left behind a clearly-defined career path in public health in Japan for a rather uncertain future in music in the United States. But 15 years after jumping head-first into music, Motoshi’s love of jazz and desire to create have made him a sought-after performer. He is spending his summer performing at the American Harp Society conference in New Orleans and the World Harp Congress in Sydney.

We caught up with Motoshi back home in California where you are as likely to find him caring for his animals, working in his garden, or practicing Judo as you are to find him sitting behind a harp. A lot of us talk about finding balance in our lives. Motoshi is living it. And if his authentic and easy-going nature are any indication, the balance he has found for himself is working out pretty well.

[pullquote]Want to learn more about Motoshi’s thoughts on improvistion? Check out his blog posts.[/pullquote]

Harp Column: I want to introduce you to Harp Column readers who might not know you. I know harp isn’t your first instrument. You played piano and guitar beforehand. Is that correct?

Motoshi Kosako: Yes.

HC: So how did you get started with harp? What drew you to the instrument?

MK: When I was three, my mother wanted me to learn piano because she thought it was good for my education. I was kind of an active boy. [Laughs] I liked playing ball inside. I went to lessons for about nine years, and I never liked it because our piano was like a little mechanical device. It’s kind of a magic box; you don’t know what is going on inside. So for me it wasn’t really interesting. When I was in the fourth grade, I started playing trumpet in a school band. The trumpet is much more interesting for me because you really make sound with your body, and whatever you do directly affects the sound. Later my older brother started playing the guitar. The guitar was kind of a cool rock ‘n’ roll instrument. So when I was 13, I quit playing piano, and I got a guitar. I really enjoyed guitar. I played blues, rock, and I was really interested in improvisation. When I went to the university, I moved to Tokyo. And I started playing jazz with the university students. In Japan we don’t have an official jazz conservatory, so we were studying something different, but after school and on weekends, we got together to play and study jazz. I was in public health, but we were playing jazz too. I wanted to become a jazz guitarist, you know there are tens of thousands of jazz guitarists. And what I felt was, I am imitating somebody all the time—as a jazz musician, as an improviser, as a composer—like Pat Metheny, like Ralph Towner, great musicians. I could imitate those people very well, but I never felt a direct connection to the music. So my relationship with music was always indirect. I always had a third person in between.

[protection_text]

HC: Yes, there’s somebody always in the middle.

MK: Yes, and as long as I was playing the guitar, I had already a built-in attitude, built-in idioms, built-in ideas or way of thinking about music. So I thought, it is not a bad idea to reset my relationship to music by quitting the instrument I am so familiar with and doing something else. And also, as a guitarist, it was difficult for me to really study classical guitar diligently because I could play already—improvisation and blues and jazz. But playing classical music, you need discipline to read, follow, and act. [Laughs] In a way you have to surrender to the idea the composer is presenting us. Not surrender, but you need to say, I agree with this, I agree with that, and try to make an effort to actualize what he is envisioning in the music. I was lacking that part of discipline as a jazz musician, as an improviser, and I wanted to develop that, but if I have an instrument that I can play well, I couldn’t force myself to do it. I thought by playing the harp I would have to start from the beginning, and I thought that by doing that I could renew and refresh my relationship to music. It was a big gamble for me. But it worked out, so I’m very happy I did what I did.

HC: Why the harp, though? You could have gone a number of directions and pursued jazz on a different instrument. So why did you choose the harp?

MK: The practical reason was, the timing was right. I met the instrument through a person I knew, so I had a chance encounter with this instrument. The other reason is, I like harmony instruments, like piano. I really like piano music as a listener, but not as much as a player.

HC: So you didn’t necessarily want to play a rhythm instrument like the drums or a melody instrument. You wanted the harmony.

MK: Yes, not just melody. I was fascinated by the world of harmony and the structure. I think that the harp was kind of the perfect solution.

HC: How would you describe yourself as a musician? And how would you describe your music?

MK: Yes, this is a very profound question. [Laughs] The style of music I’m playing is modern jazz or third stream, which means between jazz and Western classical kind of music. Sometimes it’s described as European jazz. We don’t really have an established name for it. As far as my writing, I’m trying to write something lyrical instead of abstract. I’m not writing so much abstract and atonal, but something where the tone is very clear. So that’s the kind of music I’m working on.

In the big picture, I think I am using music as one of many activities to make myself a better person, both spiritually and physically. I don’t see myself as a guy who dedicated himself to music completely. I practice; I make an effort; I try to reach out. But I ask myself this question frequently: if tomorrow I get in a big accident, I smash my hand, I can’t use this hand anymore, am I going to be as valuable as before? When I was younger I was always afraid of this scenario. Just thinking about it was so scary. So for me that kind of relationship to music is not right. It doesn’t make me a more fulfilled person. I have been pursuing a lifestyle or philosophy that I can continue to live as a more fulfilled, happy person even if tomorrow I could no longer play. In that sense music is not my straight purpose.

HC: It’s not everything. It’s not who you are.

MK: Yes, it’s one of the activities I am engaged in. As a harpist, I am not the harpist who plays jazz, actually. I played jazz before I started playing harp, so I’m kind of a jazz musician picking up the harp. I think that is a distinctive difference from most of the jazz harpists. Lots of harpists, they play the harp and then they pick up jazz. But in my case it was the opposite.

HC: So, when you starting playing the harp in 1999, you strictly studied classical repertoire?

MK: Yes, and I wrote a little bit of music. But I never tried improvisation or even played a jazz tune on the harp. I never actually played jazz on the harp until about 2006.

HC: You were born and raised in Japan, but what brought you to the United States?

MK: The Japanese society is an old society. People are aware of what you’re doing all the time. Does he talk properly? Does he behave properly? In the United States they don’t care. [Laughs] No one cares what you do. You can think or you can say whatever you want. But in Japan the social structure is tighter, and, in a way, I was not fitting into that society very well. Actually, I was doing very well—I went to the top university in Japan, which is like Harvard here. I went to the medical school and became a public health nurse and a psychiatric nurse. And I was working in a university hospital, and you can almost predict what is going to happen in your life because society expects it. Honestly, I really felt stuck. Another thing is that it is so comfortable if you are successful as a young man in Japan, and I felt spoiled in that environment. It didn’t make me a better person. I functioned very well in the society, but as an individual human, if they took me out of the society, I wasn’t sure if I’d be a valuable person or if I would become a balanced person. I had never been out of Japan until I came to the United States. I had never seen the world, in a way. So in 1997, when I was 26, I came to the United States.

HC: Do you ever go back to visit family?

MK: Yes, and I do a tour every year in Japan and workshops and everything. But, actually, I didn’t plan to immigrate at all. I just wanted experience, and I thought maybe in a couple years I’d want to go back to Japan, but I found that I didn’t fit back into the society.

HC: Well, let me shift gears a little bit. I think it’s really interesting that you describe yourself as a jazz musician who plays the harp. I think many classically trained harpists dabble in jazz or dabble in improvisation, but their main lens through which they view music is the harp. That’s who they are. So I think your perspective is definitely an interesting one. I’m curious what do you think the harp does well as a jazz instrument?

MK: You can touch the strings directly on a harp. You can control the tone, color, the sound. It directly reflects what you do. So that is the biggest advantage of the harp. And compared to the guitar, you can pluck the strings with your hands, so you can do much more complicated structural things on the harp compared with the guitar. Another thing I found very convenient on the harp is that the fingering on the left hand and the right hand are the same, so if you learn how to play something on one hand, you can just copy. That is a huge advantage. Harpists think it is so difficult to play jazz on the harp because of the modulation and the chromatic approach to the music and phrasing. In a way, I would say it’s difficult to play something like a bebop-style jazz, but if you carefully choose the modulation or chord progression to use just one or two or three pedal changes, the advantage of the harp is once you set a pedal in the right place, you have only seven notes available on the instrument. And those seven notes are right notes for the key you’re in.

HC: Yes, once you’re there, you’re there. You can’t hit a wrong note.

MK: Yes, and one difficulty in playing the traditional guitar is that all the notes are on the fingerboard. You have to pick the right position to play the note you want. But on the harp every note on the instrument is one you can use. In context, some of the notes sound weird if you do it in the wrong context or the wrong phrasing, but you can use those building blocks. You know, if you put the pedal in the right position, you skip the most difficult part of the modulation, which is choosing the right note. It’s like you have a palate, with only the right colors, so you don’t have to mix any, and that’s a huge advantage of the harp.

HC: What do you think is the most difficult thing about playing jazz on the harp?

MK: Most difficult thing? We call it jazz music and associate it with a certain type of music, but jazz is an ever-changing style of music. Let’s say the pianist is playing jazz in a way that he came up with, and it becomes like a style. Well, on the harp we don’t have many people who, in the past, tried to establish harp jazz. I’m not criticizing anybody, but as a mass, we have very few people.

HC: There’s not much history to draw upon.

MK: Exactly.

HC: You’re inventing everything, essentially.

MK: We, all jazz harpists working today, have a responsibility to contribute something and to establish what we can do on the harp. This is my personal opinion. As long as we are trying to mimic piano or guitar or existing jazz, jazz will never blossom. If you look at an instrument like guitar, there are so many different types of jazz guitarists. If you listen to the guitarist in the Nat King Cole Band and to one in the Miles Davis band, they are kind of different. The jazz guitar or jazz piano is the accumulation of all these individual contributions of each instrument. Harpists try to learn methods from jazz pianists, but it’s so difficult with the harp because we have to think about pedals, and the approach is so different. So we have to be our own pioneers and take risks and experiment and learn from trial and error, but that is the most exciting part.

HC: Yes, the most difficult part is also the most exciting. Well let me ask you, what advice would you have for other harpists, especially younger harpists, who have studied classically and want to explore jazz, but don’t know where to start or are intimidated by the whole process? What advice do you have for them?

MK: First, love jazz! I think love or enthusiasm for jazz or improvisation should be the primary motivation. Some harpists want to play jazz because you can get more gigs or because they think it’s nice to add some repertoire for weddings. If that’s your motivation, you can learn the form to play some jazz tunes. But you cannot learn the most important part of jazz—improvisation—because it’s kind of a demanding task to learn. However, if you have love or enthusiasm you can do it.

HC: The motivation has to come from the right place.

MK: Yes, you need to be emotionally involved in the activity. If you have that, you can find a way to learn it. The other important thing is that doing is the best way to learn. If you want to do it, instead of looking for a teacher or looking for a book, do it! That’s what our ancestors and other musicians did, they just did it!

HC: There was a time when there was no book.

MK:Yes, they just did it. We harpists have this permission still. And who knows, maybe later, in 20 years maybe I will come up with some very effective method for jazz on the harp.

HC: You’re certainly catching people’s attention. You’re pretty popular this summer—playing at the American Harp Society Conference in New Orleans, and then also at the World Harp Congress in Sydney. Tell us about these big plans for the summer.

MK: Yes, I am excited. I am reaching out as a harpist to see what I can do to share knowledge and ideas. It’s a good opportunity to present a different style of composition and a different way to play the harp. I don’t have any intention of hiding anything. What I can do, everybody can do. If someone is interested in knowing what I am doing I am open to teaching or talking. Unless I go there I have no opportunity to do that.

HC: I am curious, whose music do you enjoy listening to?

MK: There are so many! As a composer I have been influenced by Ralph Towner. He’s a guitarist and leader of the band Oregon that started in the 1960s. I also listen to Keith Jarrett. Those two composers/improvisers have had the greatest influence on me. Of course, jazz pianists, and Bill Evans, and lots of jazz guitarists. Recently I have been really interested in listening to traditional Indian music. You know, the tabla, the sitar, and that kind of music. That is a very different approach to music, in a way. I often use the conventional approach to the music theory, that is harmony and melody. But Indian music, or let’s say tribal music, has a totally different method—that is how you approach or how you grasp and understand the music. Indian music definitely has a totally different approach. That is very interesting to me.

HC: Do you practice? And if so, can you explain your practice process?

MK: Yes. For me playing an instrument is something like martial arts. I still do some martial arts and have a second-degree black belt in Judo. In martial arts we emphasize balance or harmonized work between the body and mind. The body and mind have to cooperate and work together. Playing an instrument is like that too. During practice my attention is more on the entire body, and playing is secondary—it is a result of how my holistic existence is. I have to practice being intentional with everything—the way I sit at the harp, what I am trying to do.

So I come up with an idea, I try it, and simultaneously I am listening. Then I judge if something is not right and then I try to fix it. Sometimes what is happening is a technical issue. Sometimes you are just playing a note that is not right. Then I go on and evaluate again and try to fix it again. And basically that is what I am doing when I am practicing. I try to do something that I have never done. A simple thing is accompanying with the right hand in the higher register while doing a bass solo. That’s just one example. Something like that. That’s how I practice improvisation.

HC: Right. And in the big scheme of things, you haven’t really played the harp that long. You’ve played the harp for just 15 years, but you’ve accomplished a great deal in that amount of time. What do you still want to do in music?

MK: [Laughs] Well, actually, improvisation is kind of an endless process of learning. Every day, every time I play it’s the same kind of challenge. The difficulty will never decrease. So I just keep doing what I have been doing. I will probably find another crossroad where I have to take a turn at some point. •